BATAVIA

The intention was that the three skippers of the expedition would sail to the Netherlands with the next return fleet in order to be able to report extensively on their journey to the people of the VOC who had sent them on this expedition (1). But since it was only mid-March and the next fleet would still be more than half a year away, they were soon assigned to another job after their long adventure. Captains were like bus drivers back then. After completing one journey, they had to perform another trip, often on another ship (2). This time, however, all three skippers kept their ships for one more trip.

Another assignment

Willem de Vlamingh and Gerrit Collaert sailed on 4 May with the Geelvinck and the Nijptangh to Bengal (present-day Bangladesh and West Bengal).

The Geelvinck carried nearly 40,000 silver ducats plus a lot of cloth, copper and mace.

In addition to goods, the Nijptangh had slightly more than 25,500 guilders in cash on board.

Michiel Bloem, who had been Willem van Vlamingh's chief mate on several voyages, also accompanied him this time, but did not survive this voyage and died on 14 September in Bengal (3).

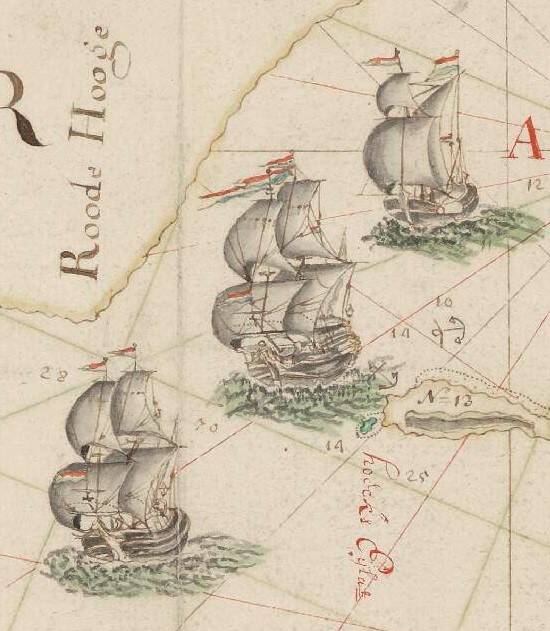

The three ships drawn on the map which was made of the coast of the Southland

Michiel Blom in Bengalen overleden (Michiel Blom died in Bengal). See: National Archives in The Hague under VOC, the section Overgekomen brieven en papieren (Transmitted letters and papers), 1.04.02, inventory number: 1589, (section: Batavia, page 1232 (= scan 125))

Recent postage stamp from Moni (the current Christmas Island) on the occasion of this voyage of Willem de Vlamingh

Cornelis also stayed at the helm of 't Weseltje for a while longer after his trip to the Southand. He was instructed to first return to the island of Moni (which the expedition members had skipped on their journey) to further investigate what exactly could be found there. It was understood from Willem de Vlamingh's logbook that Moni had tall trees from which good masts might perhaps be made for VOC ships. Cornelis was sent back to take a few with him, preferably as many as he could store. Also on board with him were eight natives (4 from Maccassar and 4 from Mardijk) who had to cross the entire island in search of fruits, herbs, fresh drinking water and everything that could be of interest to the company. Because what could not be found in the Southland, could perhaps be obtained much closer on this island.

However, around May-June 1697 the weather suddenly became so bad that Cornelis de Vlamingh could not come ashore on the island of Moni (4). He returned to Batavia empty-handed. This expedition was also considered a failure by the VOC.

Immediately afterwards, Cornelis was sent to Bengal with't Weseltje and a lot of cargo to join the others.

Even more chores

Unfortunately, the former expedition members returned a bit too late from Bengal. It took them more than six months to get back to Batavia and by then the preparations for a new return fleet to the homeland had already been completed. Claes Bichon had already been appointed as commander of the new returning fleet to Holland, a prayer day had already been held twice and all skippers involved had also received the traditional farewell meal when Willem de Vlamingh arrived in Batavia with the Geelvinck on November 23, 1697.

Although the three of them left Bengal at the same time, Willem was already back in Java for almost a week when the Nijptangh and 't Weseltje arrived. This was way too late to join the upcoming fleet that was sceduled to depart on November 30 (5). The Nijptangh still had to be unloaded. Maybe interesting to know it was not only transporting a cargo of wheat and saltpeter, but also opium!

We are sure our three skippers - Willem and Cornelis de Vlamingh and Gerrit Collaert - made this extra trip to Bengal. However, as soon as they returned to Batavia, the ships are immediately sent out again. From December 3 to 11, the Geelvinck is sent after the returning fleet just to deliver various papers and 't Weseltje departs from December 14 to 18 for a trip to Bantam to ask the lieutenant governor there what kind of gift the VOC administration could best give to the sultan. We are not sure whether Willem and Cornelis actually made these trips or whether other skippers were now steering the ships.

View of the city and castle of Batavia, drawn by Johannes Nessel (in 1650). More about Batavia Castle on Wikipedia

Fact is, the Nijptangh did not get another captain until January 8 and our three skippers did not finally leave with another returning fleet back to the Netherlands until February 11: Willem de Vlamingh as skipper on board the ship de Gent, his son Cornelis on the Boor and Gerrit Collaert on the Carthago (the latter two both in a lower rank than skipper).

Failed

So the three skippers of the expedition to the Southland were not themselves present on the first fleet that sailed to the homeland, but their logbooks and all found objects were given to Commander Claes Bichon on the ship 's Lands Welvaren. Perhaps the fact that Willem de Vlamingh could not immediately explain his findings contributed to the VOC's negative assessment of the trip. In Amsterdam people were not at all satisfied with the results of Willem's journey to the Southland.

Firstly, the VOC board members found it extremely disappointing no shipwrecked sailors or old wrecks (with chests full of money on board) had been found. The Vergulde Draak, for example, had 78,000 guilders worth of gold and silver on board! No wonder the VOC continued to look for it, even forty years later. Although it was of course a vain hope to ever find anything of those ships again. Even after all this time, it still feels unfair to us to blame Willem de Vlamingh for the fact there was nothing left of it.

In addition, the entire enterprise was considered a failure because no riches had been discovered in the Southland, nor were there any cities to trade with. So there was nothing to bennefit the VOC. But where there is nothing, there is nothing to be found, right?! So in our opinion this is by no means Willem's fault. He did everything humanly possible. (Just for the record, the VOC also thought Abel Tasman's voyage of discovery was a failure!)

All the little trinkets that were given to the ships to trade in the Southland were publicly sold in Batavia after the voyage. Most of it was a loss, because some items were already damaged, in poor condition or completely unwanted. The purchase had originally cost the VOC 2,511 guilders, but the goods now only fetched just under 1,716. A loss of almost 800 guilders.

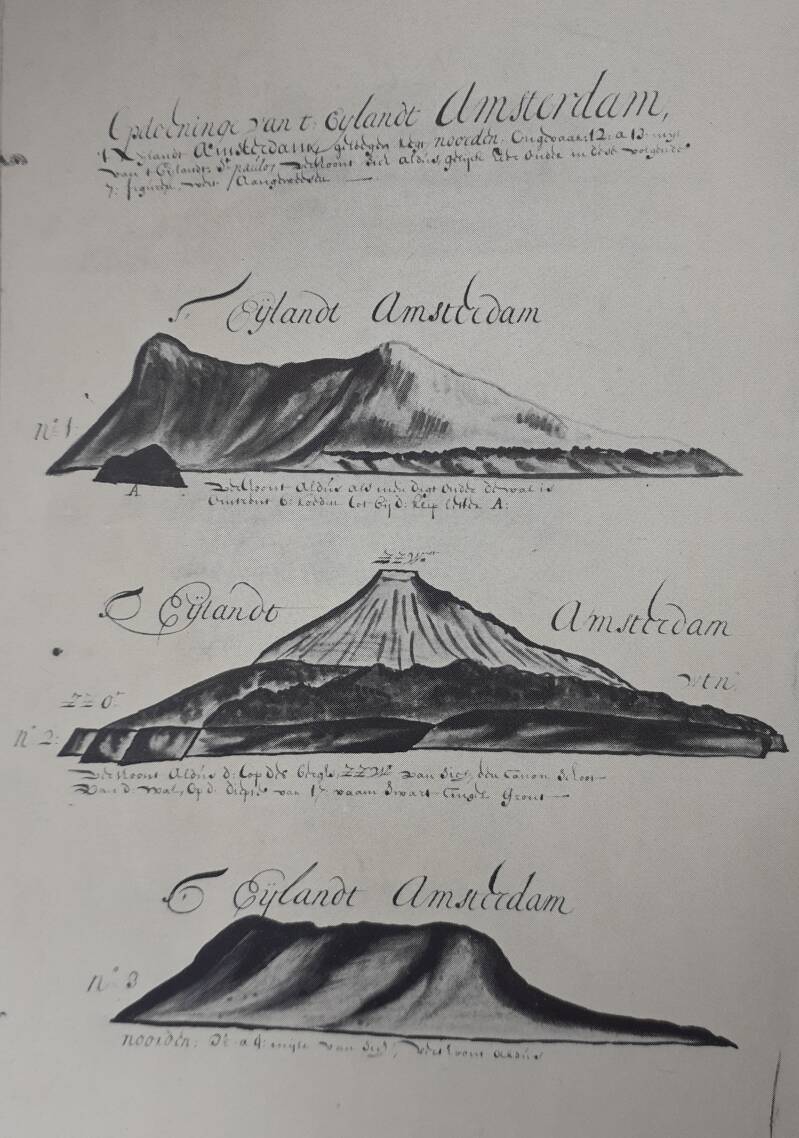

There was more loss, because not everything the expedition had delivered reached the clients. For example, Commander Bichon simply took the watercolors that draftsman Victor Victorszoon had made to his own home! It involved no fewer than eleven paintings (6) depicting various places on the Southland and all the islands they visited along the way, even one from the island of Moni which was not part of their assignment (7). These watercolors were lost for centuries, until Günter Schilder found them in the Maritime Museum in Rotterdam in 1970.

One of the recovered watercolors by Victor Victorszoon (from the island of Amsterdam)

What the clients in Amsterdam did get their hands on did not appeal to their imagination. In addition to the three logbooks, there was also some scented wood and the bottles of oil which had been made from it. But the Governor General of Batavia already warned the VOC in the Netherlands in an accompanying letter (8) he in Batavia already could no longer smell the odor of the wood.

In the opinion of the governor, the cabinet with shells, fruits and crops etc, collected on the beach of the Southland, are no good either. According to him, these products can even be found of better quality elsewhere in India.

The three black swans Willem de Vlamingh had captured and delivered to Batavia alive, had all died in Java.

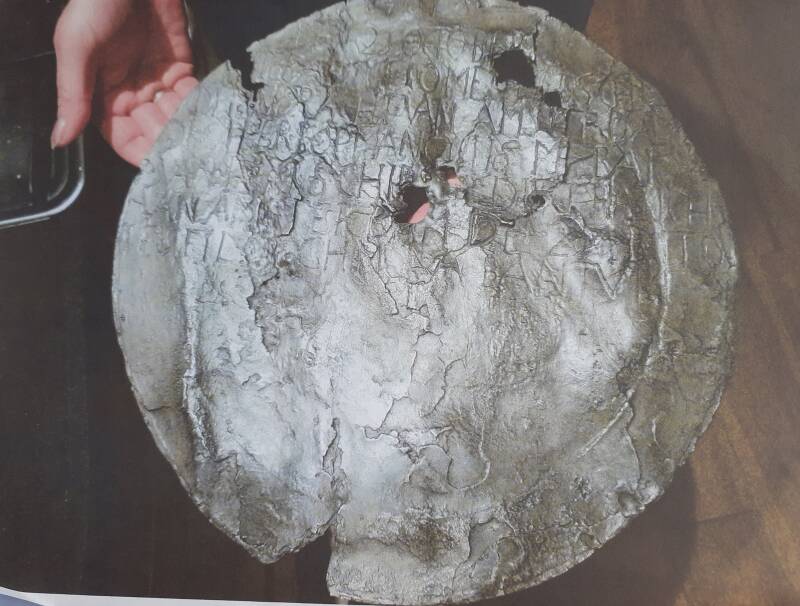

All that remained was the pewter dish Dirk Hartog once left behind in the Southland and which the recipients in Amsterdam could now admire.

The governor of Batavia already knew what the VOC in Amsterdam would think of the trip to the Southland and tried to put in a good word for the skipper. He concludes it's a pity there was nothing but barren, barren, desolate land to be found in the Southland. Still this is not the fault of Willem de Vlamingh. In the point of view of the governor the leader of the expedition carried out his assignment correctly and observed the foreign country well in accordance with his instructions. in our opinion this was a very justified conclusion: the expedition had produced perfect maps of the entire west coast of Australia, which meant that from now on far fewer ships would get shipwrecked on that coast! (9)

Willem de Vlamingh mapped a large part of the west coast of Australia, which resulted in far fewer ships running aground. The National Archives in The Hague have a map of the Indian Archipelago showing the discoveries of Abel Tasman in 1644 and those on the west coast of New Holland by De Vlamingh in 1697. (Hollandia Nova by Isaak de Graaf)

However, Mayor Witsen's assessment was damning. In a letter to the Englishman Martin Lister - a doctor and naturalist - Witsen concluded: On this voyage nothing hath been discovered which can bee any way servicable to the compagny (the Dutch Mayor wrote the letter in his best English) (10).

Nicolaes Witsen, who had expected a lot from the entire undertaking and had bragged about it to everyone, was extremely disappointed in the results and accused Willem de Vlamingh of laziness and laxity. For example, according to Mayor Witsen, the expedition leader, against his express instructions, would not have been anywhere in the Southland for more than three days (which is not true at all).

In his frustration he even describes Willem de Vlamingh as an alcoholic. In his opinion, the commander had been a drunk and had spent his time at the Cape with banquets and merrymaking (11).

We become vicariously angry when we read these false accusations. In our view, William de Vlamingh had carried out all his actions very precisely, including the enormous detour to the islands of Tristan Da Cunha, under extremely harsh conditions, so many of his men had become ill and his ship had to be repaired. That is why they stayed longer than average at the refreshment station at the Cape. So on second thought it was Witsen's own fault: he had added this extra detour to the instructions of the expedition at the last minute.

Because the VOC judged the trip as a failure, Willem de Vlamingh unjustly remained a completely unknown person in Dutch history books. In our opinion, the accusations made are all incorrect and he deserves more recognition, fame and even some form of rehabilitation!!

In Holland, Willem de Vlamingh now only has a street sign in Hilversum and on Vlieland. In our opinion there should be many more!! Also in other countries...

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb