THE SOUTHLAND

Saint Paul and Saint Peter

On their way the south, our little fleet, as expected, encountered two islands - St. Paul and St. Peter - which were subjected by them to a thorough inspection from November 28 to December 5, 1696, in accordance with their instructions.

This inspection makes Willem de Vlamingh, according to Professor Hacquebord, the first human to ever set foot on these islands!

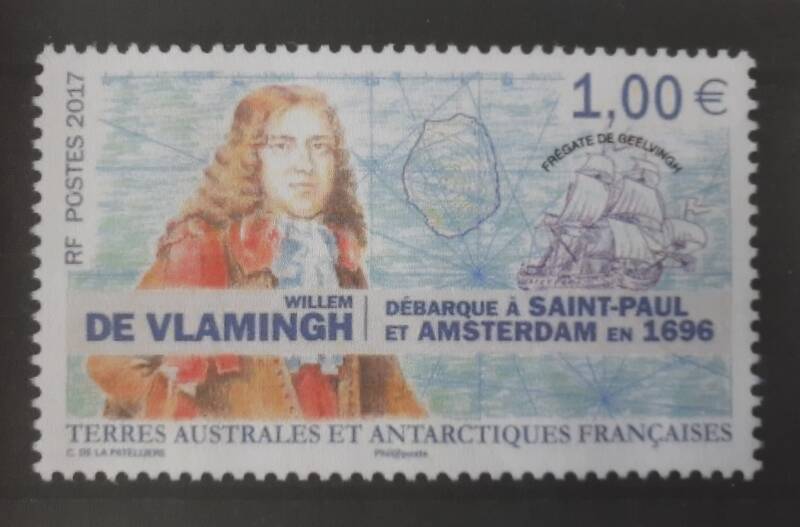

Postage stamp from 2017 and contour sketches made by Victor Victorszoon during the trip

The islands were originally called Saint Peter and Saint Paul, but some lame Dutchman renamed the island Saint Peter "the Amsterdam island" - how arrogant and also very confusing!

Although this is a nice thought (that Willem de Vlamingh entered these islands as the first human ever) , we surely doubt it, because commander Hendrick Pronk - as we saw earlier - was also instructed to search those islands for shipwrecked people (maybe, just maybe no one went ashore of the Hendrik Pronk crew and so we award Willem de Vlamingh this scoop).

As commander, Willem de Vlamingh had barley and peas planted on the islands for any future castaways. In addition, they placed a tin sign on a pole in the ground with the text that they have been ashore and are now sailing on in search of the great unknown Land in the South.

Rottnest Island

T Eijlant T Rottenest mapped during this trip of Willem de Vlamingh

On December 5, the three ships sailed on and in the last days of the year they finally got their final destination in sight, for which God in heaven be thanked. There was a terrible fog, so they couldn't go ashore. When the fog lifted the next day, they discovered not to be floating off the coast of the Southland, but on an island just off what is now Australia.

At first they called the island Mistland because of the dense fog, soon however they renamed it Rattennest Eiland (now Rottnest Island) after the many large "rats" roaming around. Nowadays we know these cat-sized beasts are not rats at all. They are quokkas, a type of dwarf kangaroos.

Photo by Jan Houter of the monument to Willem de Vlamingh on Rottnest Island

The West Coast

In the first days of the year 1697 they finally reached the Great Southland. Willem de Vlamingh wrote in his log he immediately feels at home, because the coast consists of rough-growing sand hills, which have the shape of Vlieland's dunes. Yet, when they got ashore, the inhospitability of the area disappointed them.

Right at the place where they arrived, they saw the estuary of a large river. At first this stream was called the Witsen River. Soon afterwards it is renamed into Swarte Swaene Revier, which is an oldfashioned Dutch way of saying "Black Swan River", (nowadays just Swan River).

The place was namely crowded with swans. And not just any swans. These were black ones! A discovery that shook the world to its foundations. Until then it had always been assumed all swans were white, since only those were known in the West. In fact, if something was an established fact, you could say “because swans are white” in the sense of a full stop, end of discussion.

The discovery of black swans

An earth shattering event!!

In economics, a "black swan" denotes an unexpected event, something no one anticipated or predicted in advance.

John Gerrard Keulemans, 1869

On January 5, a number of expedition members went ashore with a group of no less than 80 soldiers armed with rifles (1). They followed the banks of the Swan River, spent the night on the mainland and then returned to their ships. A number of men ate a fruit that looked a bit like a kidney bean, but turned out to be quite poisonous. Chief Surgeon Torst and five others tasted it. In retrospect, we now know it was the nut of the Zamia palm. After 3 hours of vomiting, the victims were more dead than alive, but thankfully they all survived.

On January 9, they decided to sail up the river with rowing boats. Willem de Vlamingh and a number of other expedition members sailed up the river in sloops. They did discover traces of footsteps, a dilapidated hut and remains of an extinguished campfire, but the scouts saw no indigenous people anywhere and that was quite disappointing to them. After all, they had hoped to find rich cities - such as on Java - with which to trade. Instead they found an empty and desolate land full of rocks and dry bushes. Oddly enough, they did not even seemed to find any kangaroos, which Australia is now so famous for.

The VOC wanted the expedition members to explore and map ten degrees of latitude of the Great Unknown Land in the South. Willem de Vlamingh carried out this important task very meticulously. The coast has been drawn on a nautical chart, watercolors have been made by Victor Victorszoon, the depth of the seabed has been sounded and every day people rowed with sloops to the coast to explore the land. In addition, they set off a cannon every half hour to let any castaways know they were there.

There are people who claim it was precisely these cannon shots that ensured no original inhabitants were ever encountered. In any case, the explorers saw no one during the entire journey, except once. On January 23, the land scouts reported they had seen no less than ten indigenous people standing on the beach, while they themselves were sitting in their sloop. Unfortunately, the surf was too strong, so the Dutch could not come ashore at that time. This only succeeded a mile away, but by the time the expedition members arrived at the spot, there was no trace of the residents of the Southland.

The scouts had observed the ten men on the beach scrupulously from a distance. Gerrit Collaert (the captain of the Nijptangh) describes the Aborigines as follows: They are the poorest people in the world, they resemble monkeys, are tall and straight, very thin, have long limbs, large heads with a round forehead and huge eyebrows. Their eyelids are always half-closed to keep the flies out of their eyes. Big blunt noses and wide mouths with thick full lips. In addition, they also have stiff erect hair and a soot-colored skin, badly painted. More factually, Willem de Vlamingh just states in his logbook his men reported seeing 10 people, very naked and black without any guns.

The intention was to catch an Aboriginal... Nicolaes Witsen wrote in a letter dated March 12, 1696 to his friend Gijsbert Cuper about the venture to the Southland: I have already given orders to get a Southlander and to transfer him to the Netherlands if possible. Fortunately, they never caught one!

Dirk Hartog Island

On January 30, the expedition members recognized the contoures of "Houtman's Abrolhos" - probably from descriptions and drawings the seemen had received from the VOC. Houtman's Abrolhos was the place where skipper Dirk Hartog of the Eendracht once set foot. Frederik Houtman had been the helmsman of the Eendracht and Abrolhos meant as much as "Keep your eyes open" (from the Spanish abre for opening and ojos for eyes). This warning to helmsman Houtman from long ago was not in vain. There were many dangerous reefs there in that place.

Dirk Hartogs eiland mapped during this trip of Willem de Vlamingh

The brave expedition members - including Willem de Vlamingh himself - also landed here. Michiel Bloem, the chief mate of the Geelvinck, climbed a hill for a better view and found a half-decayed post with a fallen sign underneath. It turned out to be the tin dish Dirk Hartog and his men had left there eighty years earlier! A unique find.

Willem de Vlamingh decided to take Dirk Hartog's plate with him on board and leave his own engraved dish at the same place. Today this pewter plate by Dirk Hartog can be viewed at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

On the plate of Dirk Hartog it read (in translation):

1616. On October 25th the ship Eendracht came here from Amsterdam, with merchant Gilles Miebais from Luik, skipper Dirk Hartog from Amsterdam. Sailed on ditto 27th to Bantum. Assistent merchant was Jan Stins and upper steersman was Pieter Doores from Bil. Anno 1616

On the new board the expedition members put up, they repeated the text of Dirk Hartog first and added the following inscription (in Dutch):

1697 den 4 februari is hier aangekomen het schip de Geelvink voor Amsterdam, de commandeur schipper Willem de Vlamingh van Vlielant, assistent Johannes van Bremen van Kopenhagen, opperstuurman Michiel Blom van Bremen, de hoeker de nijptangh: schipper Gerrit Collaert van Amsterdam, assistent Theodorus Heermans van dito, opperstuurman Gerrit Gerritsz van Bremen. ‘t galjoot het Weseltje, gezaghebber Cornelis de Vlamingh van Vlieland, stoerman Coert Gerritsz van Bremen en van hier gezeild met onze vloot de 12e dito voorts het Zuidland te onderzoeken en gedistineerd voor Batavia.

Translation:

1697 on the 4th of February arrived here the ship the Geelvink for Amsterdam, the commander skipper Willem de Vlamingh from Vlieland, assistant Johannes van Bremen from Copenhagen, chief mate Michiel Blom from Bremen, the Nijptangh: skipper Gerrit Collaert from Amsterdam, assistant Theodorus Heermans from ditto, chief mate Gerrit Gerritsz from Bremen. And galliot the Weseltje, steersman Cornelis de Vlamingh from Vlieland, helmsman Koert Gerritsz from Bremen and sailed from here with our fleet the 12th ditto to further investigate the South Land and are destined for Batavia.

Incidentally, this dish of Willem de Vlamingh and his men was discovered almost two centuries later by a French expedition. The French crew decided to leave the dish hanging out of respect, but later others took the tin plate with the inscription of Willem de Vlamingh with them and finally, after many wanderings, the original can now be admired in the WA Maritime Museum, located at the estuary of Swan River on the west coast in Australia where Willem de Vlamingh first landed. Copies of both dishes can be seen in the Museum Tromp's Huys on Vlieland!

Hazardous times at the Southland

On their further exploration, Willem de Vlamingh and his men experienced all kinds of exciting adventures, for example they anchored in a bay full of sharks, had to avoid cliffs and regularly went on expeditions on land where there was hardly any drinking water, where wild animals were lurking and the chance of getting lost was very big. If you can read Dutch, you can find out all about it in my book.

Dislodged

On Monday, January 7, 1697, the anchor rope of the Geelvinck snapped. At that time, the expedition members had only been ancoring for one day in front of the coast of the Southland and a group of about a hundred scouts had gone ashore on their first voyage of discovery. Among them was also the chief mate of the Geelvinck, Michiel Bloem.

Willem de Vlamingh was waiting off the coast for his men to return to report on the new found land when suddenly his anchor rope broke. This immediately put the crew on board the Geelvinck in a life-threatening situation. As soon as the anchor no longer holds a ship in place, it is at the mercy of the elements and the boat drifted with the waves.

A model of the Geelvinck build by Captain. J. Horjus displayed in the attic of the Tromp's Huys museum

It always takes a while to hoist the sails on such a large ship and to get a grip on the direction of travel. This could have turned out very differently and the Geelvinck could have crashed against the coast. Fortunately, the wind was in the right direction and the incident ended with a fizzle.

Capsized

A month later, they again escape a very dangerous situation. On February 7, a sloop capsized near Dirk Hartogsree (which is about 500 miles north of Swan River, in present-day Perth).

Willem de Vlamingh was on land with a large group of men on this day to subject the interior of the Southland to a closer investigation. The three ships waited off the coast for the whole group to return.

This beautiful illustration by Arnold de Lange was only just finished and yet we were already allowed to place it here on our website. FANTASTIC!! Here you can see the three ships, historically correct in every detail, lying in front of Dirk Hartogs island along the west coast of the Southand.

In the meantime there was plenty to do for everyone who stayed behind on the ships. The accountant together with the second mate of the Geelvinck went ashore with a sloop and another sloop of the Nijptangh was used to gauge the depth of the water. Cornelis de Vlamingh and his second mate were on board this last boat, which had a sail. At one point, Cornelis decided to sail even closer to the coast when he was suddenly caught by a gust of wind coming from land. The sloop suddenly got wind from the other side in its sails and capsized! In his log his father Willem de Vlamingh used an old Dutch word - omgezeijlt - we had to loot it up. Although this happened within sight of the coast, it was truly life-threatening for most of them, as sailors generally could not swim at that time (2).

The lemma of the old Dutch word (unknown to us) "omzeilen" in the Lexicon van de Zeilvaart (this is a Lexicon explaining all kinds of words about sailing), with thanks to Dirk Stolp of the Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam for sending us this picture

Crew members of the Geelvinck saw the accident happen and sounded the alarm. They waved a signal flag and fired three cannon shots, hoping to warn the few men who had just gone ashore. It worked. The men of the sloop from the Geelvinck immediately hurried from the coast to the capsized sloop. People on board the galliot were also aware of the danger. They lifted the anchor, hoisted the sails and reached the capsized sloop first. Fortunately, they were quick enough and could save everyone on the capsized sloop. Only the galliot's carpenter died in this event, as one of the ropes of the heavy leads slipped off and apparently killed him. As a result, the carpenter eventually drowned (3).

In retrospect, it turned out Willem de Vlamingh did not hear the cannon shots on his journey ashore at all. He did not return until a few days later and then learned of the frightening event in which he could easily had lost his son and several other crew members as well. He promptly gave one of the carpenters of the Geelvinck to his son for the maintenance of 't Weseltje (4).

Willem de Vlamingh describes the incident extensively in his log. The most moving sentence is this one:

Can you read the Dutch handwriting? It says: ...om hooghte te neme en een weijnig daerna is de gesaghebber van 't galjoot na de wal van 't Eijland woude zijlen en bij ongeluk door een valwind over 't land komende omgezijlt...

So this sentence talks about the steerman of the galliot who wanted to sail to the shore of the island and was accidentally knocked over by a gust of wind coming over land. A rather cold-blooded observation when we bear in mind this steerman of the galliot is Cornelis de Vlamingh, Willem's very own son, who in this incident narrowly escaped death!

In the Consumptieboeken van de VOC (these so called "Consumption Books of the VOC" are kept by the National Archives in The Hague), we read in Dutch:

...aldaar per ongeluk met 't omslaan van de schuijt een zeevarende verlooren, dog daar is tegen van 't opgenoemde fregat de Geelvink weder een ander bekomen...

So, the galliot 't Weseltje had lost a carpenter due to the accidental overturning of a sloop and they then got one of the carpenters from the Geelvinck for maintenance on board the galliot.

In a hurry to Batavia

On February 20, 1697, the small fleet finally reached the 20th parallel and they were able to leave the miserable Southland (as Willem de Vlamingh put it in his log). They were so happy their task is finally done, Willem lets out no less than 5 cannon shots as a farewell.

Promptly they set course for Batavia, where they arrived a month later. On their way, the expedition members passed the island of Moni (the current Christmas Island), but because Moni was not on their assignment and there was no good anchorage to be found, they only visited it briefly on March 6. We think the men were just fed up with the long journey and wanted to get home as soon as possible.

The three ships drawn on the map of the Southland in 1697. See the National Archives in The Hague, inventory number 509

Even before they arrive in the port of Batavia, a message travels ahead of them, telling the governor the three ships of the Southland expedition have appeared in the Sunda Strait. The message also conveyed they did not succeed in getting any sign from the lost ship the Ridderschap (5).

At the same time the high lords in Batavia received a letter from Willem de Vlamingh himself via a faster ship than his own Geelvinck, containing a report of the most important events of his journey. He probably only told what the VOC could find in the affected places in terms of possible food, wood and drinking water. For those are the only facts recorded in the annals at the castle.

Towards the evening of 17 March, the Nijptangh and 't Weseltje arrived at the Batavia roadstead, while the Geelvinck only arrived three days later. From the consumption coupons that indicate how much meat, bacon, olive oil and butter was consumed on board (6), we can also deduce the number of deaths from the Cape of Good Hope till Batavia:

De Geelvinck returned with 89 seafarers, 33 military personnel and 3 natives, thus losing 11 seafarers. The Nijptangh had lost 8 deaths and 't Weseltje only 1 (the aforementioned carpenter).

Map of the journey from Texel, via Tristan da Cunha to the Cape and then via Saint Paul and Saint Peter to the west coast of Australia and further north to Batavia

These consumption records also show there were no less than 12 officers on the Geelvinck who enjoyed a double ration and 8 people ate in the cabin (their names are not mentioned, but Willem de Vlamingh will certainly have been one of them). Almost as much wine and brandy were drunk during the journey by these men in the cabin as by all the people on board put together. The ordinary crew only got a sip of brandy in wet and "dirty" weather, or when they went ashore on an expedition and a sip of brandy was also seen as a medicine to strengthen the sick. More than 2000 jugs of brandy and almost 650 jugs of wine were consumed on board the Geelvinck.

Here is the main result of this whole journey - a very detailed map of the west coast of Australia:

Beautiful map, which can be found in the National Archives (inventory number 509), titled: Map of the Southland sailed by skipper Willem de Vlamingh, in the months of January and February, Anno 1697, with the yacht the Geelvink. The hoecker de Nyptangh. And the galliot 't Weseltje etc. [We chose to have the north pointing upwards, so the west coast is easily recognizable in the picture. Many of the other details can be found elsewhere on this website]

Portrait of Willem de Vlamingh??

It is worth taking a closer look at this map made on board. In the cartouche next to the text 'Duytsche Mijlen is Voor Een Graadt' there are two drawn men together with the most important navigation instruments of that time. The figure on the right holds a plumb line on a long rope; with such a heavy lead ball one could measure the depth of the sea beneath the ship. The person on the left has a compass in one hand and a so-called astrolabe in the other with which angles could be measured and thus the height of the stars could be determined. Next to him on the ground, in addition to a globe, is also a Jacob's staff (that staff is the predecessor of the sextant).

More interesting is the figure on the left itself. Especially when one considers that this map was made during the voyage on board the Geelvinck (or shortly afterwards - at least it was made in 1697). Would it not be plausible that the figure next to the globe depicts the skipper and expedition leader of the great voyage to the Southland? This - to us - is an exciting assumption, because then it is an image of none other than our Willem de Vlamingh himself!!! In that case, Willem had brown hair and a slim build. We can also see what kind of clothes he was wearing. And he probably even had a moustache .

So, what do YOU think: could the figure on the let be Willem de Vlamingh??

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb