RETURN FLEET

In the meantime, Willem de Vlamingh himself was still staying in Batavia. The governor general there greatly appreciated the old expedition leader and Willem was named the admiral of the next return fleet. This was the highest possible honor for a skipper in the VOC! Willem de Vlamingh was now one of the oldest skippers of the company and had built up an enormous record of service, but in our opinion his appointment as commander of the return fleet was mainly a reward for his work as leader of the expedition to the unknown land in the South, Australia.

The 57-year-old skipper made such a weak and elderly impression, it was feared he would not survive the journey back to the Netherlands - which could easily take six months. Just to be on the safe side, the VOC appointed a second skipper on board de Gent, a chap called Willem van Tessel, to assist the old skipper Vlamingh (1). Two captains on one ship, to us this seems unique in history!

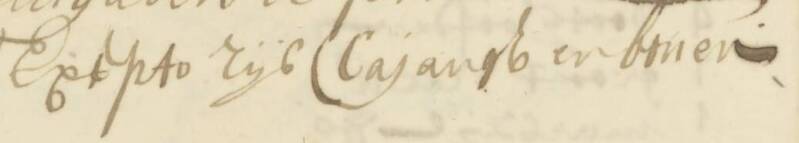

From a statement which Willem de Vlamingh signed in Batavia for the proper loading and delivery of the return ship de Gent (2) we can deduce he did not leave the work to his second at all. Instead, he took full responsibility himself. Among all the lists of provisions, cargo and crew, we also found a small note about this in the VOC books, probably written by a clerk:

See: National Archives in The Hague, VOC Third book Batavia from 1698

In Dutch the text reads: I, the undersigned Willem de Vlaming Skipper on the ship the Gent, acknowledge that this ship is properly loaded, and that the goods have been stacked and stowed to my satisfaction and that I have been provided with all the ship's needs in addition to the provision for 130 heads for 9 months without needing anything more (3).

This declaration was signed by Willem de Vlamingh personally on February 3, 1698. This shows he took full responsibility for everything on board and was totally in charge himself.

Lists of things on board

We have various sources that can give us a clear picture of what goods were present on the ships, what was eaten on board, who sailed with them, etc. As we are keen on everything related to Willem de Vlamingh we now delve deep into the archives, because all these pieces of information together can provide an increasingly complete picture of his life, or at least of the work Willem did. So get ready for some boring lists:

Goods

All sorts of lists clarify what kind of cargo Willem de Vlamingh was carrying on the ship de Gent back home to the Netherlands (4), such as black resined pepper and 1,250 bags of saltpeter. Or other intriguing things like 600 boxes of bar copper and 60,000 Siam of wood (we have no idea what these two items mean exactly).

We also know where in the hold all the items were located: for example between the bulkhead and the main mast. There you could find Bengali coffee, canvas and floral fabrics, among other things. On the other side - between the main mast and the bulkhead of the water hole - in addition to "badgers", they also stowed things called salimpouris, siams and guinea. These were probably all special types of fabric, including a lot of silk with all kinds of patterns: floral, checkered or with cables. Also new models and new silk in kind. These chests, together with 49 bales of cinnamon and 60 Javanese camphor, formed the bottom smooth layer in the hold of de Gent.

A second - also smooth - layer, consisted of even more bales of cinnamon (almost 150 pieces) and other types of fabrics, such as gingam and durias, plus half and whole yarns of silk. In between were placed 3 boxes of ammonia. Which made it a quite an incendiary cocktail there in the hold.

The third layer consisted entirely of more than 200 bales of cinnamon and the fourth layer was also completely made up of almost 200 bales of cinnamon. Plus another 184 in the fifth layer (in total there were no fewer than 800 bales of cinnamon alone in the entire hold!). In any case, there was a lot of stacking, because to this last layer no fewer than 3,309 bales of nutmeg were added, in addition to mace, white pepper and samples of Indigo (a blue dye for dyeing fabrics).

See: National Archives in The Hague, VOC Third book Batavia from 1698

On top went more Japanese and Chinese silk, damask and other exotic fabrics. By then the hold was full. In total, this ship alone transported for fl.349,732 guilders plus a number of pennies worth of goods (5)! Anyone who thinks this is a boring list should imagine how fantastic it must have smelled with all these aromatic spices on board! A scent that accompanied Willem de Vlamingh every month at sea.

Crew

After the lists of goods that were on board of de Gent for the return journey to the homeland, a list of all crew members follows in the archives (6). Of course, Willem de Vlamingh from Vlieland is the first to be mentioned as skipper, immediately followed by Willem van Tessel as the second skipper. From the data we can conclude that skipper Willem van Tessel originates from a place called Muiden (and therefore not from Texel as his surname suggests) and we can see he sailed from Enkhuizen to the East in 1697.

See: National Archives in The Hague, VOC Third book Batavia from 1698

In addition to these two captains, we count 13 other crew members on board of de Gent, including 5 helmsmen, 3 surgeons and 4 carpenters. Most of them are born in Amsterdam and the rest clearly also come from the Netherlands: from Kampen, Kempen, Woerden and Utrecht.

There is also a list of “families” who sail on board of de Gent. Such as sub-merchant Mijndert Vos. This is a citizen who has paid board and transport money to be treated in the cabin. Another citizen travels back to the Netherlands in this way together with his wife (they also payed for board and transport). At the end of the list are two male assistants, two dismissed first mates and the son of a deceased skipper who are all transported back home by the VOC.

Finally, a whole list of released soldiers (7) and so-called Impotents (disabled people) travel on board de Gent, such as a carpenter, a cooper, a bricklayer and a sailmaker. In total there are more than a hundred men. There are also ordinary citizens on board the other return ships (8).

In Dutch the text reads: Rolls with the names of the released soldiers on the aforementioned ships

Tools and food

After the list of goods and people on board, a letter follows from the accountant of de Gent (9). He states they have no less than 760 rix-dollars worth of items and cash with them from a merchant and shopkeeper named Christophel Lurelius (10). The VOC accountant promises to keep the accounts carefully and signs with the name Mijndert Vos (that is the same sub-merchant who payed to be allowed to eat in the cabin during the return trip).

Anyone who thinks we already coverd every possible item that can be recorded on board of a ship, is wrong. A very extensive inventory of all equipment on board still follows (11). This includes ammunition and tools, as well as all food for 130 people for 9 months (until they hoped to arrive at a new refreshment station). This list does not even include all the rice, peanuts and beans they already take with them for no less than 10 months.

Text in Dutch: Except rice, katjang (Indonesian word for peanuts) and beans

Anyone who reads through this inventory will come across all kinds of things, like all sorts of anchors, rope, bolts, rings, tackles. In addition, hammers, scrapers, awls. A separate section with all kinds of sails. Buckets and watering cans to keep the boat clean. Pitch and soot to tar everything and protect it from rotting in the water. Cannons with their chassis to defend the ship against attacks. All muskets, pistols and hand grenades, plus the many bullets, gun powder and fuses, also serve this purpose. The molds in bullet shape and the large gunpowder funnels suggest people made their own bullets on board. Or else an explosive mixture could be prepared with the barrels of charcoal, sulfur and saltpeter in the ten braziers and 8 fire buckets.

The war supplies change smoothly into all kinds of tools for the carpenter, bottler, cooper and helmsmen, up to and including the curtains, trumpet and Bible for the cabin.

Thanks to this complete inventory, we now know the men mainly lived on rice, beans and peanuts. With also lots of meat and bacon, butter, olive oil and vinegar, brown sugar, powdered sugar and salt. In addition, food is stocked for the livestock, in this case 32 pigs. In those days, animals were boarded alive, kept in the hold and slaughtered along the way. This way fresh meat was available. This inventory - which was probably drawn up by the accountant - was personally signed by Willem de Vlamingh.

An expense account was drawn up for everything purchased in Batavia, neatly broken down by where it was bought. Apparently there was both a large and a small store in Batavia and also a separate store for medicines. For specific goods one had to go to the iron, grain or provisions warehouse respectively.

Text in Dutch: From the Medicine Shop

In total, more than 1,800 guilders worth of items were purchased and Willem de Vlamingh as skipper again signed for recieving it all, this time together with Mijndert Vos, the sub-merchant.

Waterworks

In the castle of Batavia, the high lords of the VOC also considered the use of the water maker, which could turn salty seawater into fresh drinking water (12). They asked all skippers who had such apparatus on board about their findings with the device. It involved more than ten skippers, including not only Willem de Vlamingh, but also Gerrit Collaert (so there was also one on board the Nijptangh during the trip). All find this new invention very useful, necessary and profitable.

However, a water maker does need a lot of firewood to boil the water. On the one hand, there is always a lot of wood on board a ship, the high lords argued, including to prop up the loose items in the hold, as well as the wooden hoops of the beer pipes and other food barrels, as well as the chips and shavings of the cooper and carpenter.

The names of all captains who worked with the waterworks

National Archives in The Hague: 1.04.02 (VOC), 1589, page 1653 verso

But actually this is only the case on ships coming from the homeland, because on returning ships the hold is full of soft bales filled with pepper and other goods and they do not need to be propped up. In that case, there is not enough space on board to stow firewood.

So the question arises whether the VOC is prepared to leave part of the cargo (which generates money) behind in order to store firewood for the boiler, but less money yield could of course not be the intention. Their conclusion is that a watermaker was given to them by God to help the inner man, especially on long journeys, but not to deprive man of the better (and by this they mean the valuable commodity that would otherwise have to be used for firewood). All in all, a watermaker on board simply took up too much space, they concluded in the end.

Instruction

Willem de Vlamingh also received instructions for the return journey. This time from the gentlemen from the castle in Batavia. His orders as skipper on this return voyage cover no less than 27 pages! (13)

All skippers are urged to stay close to each other as a return fleet, because this poses less danger in the current war with France. In this way, one can better resist the violence of possible enemies and support and assist each other in need to arrive safely in our beloved Fatherland.

Skippers are repeatedly urged to be careful not to mistake enemy ships for friends (because the enemy could falsely fly the Dutch flag) and thus avoid being lured into a trap. In addition, one must pay close attention to the danger of fire and light on board, so that no accidents occur as a result.

In the same words as last time, it is recommended to sail up past Madagascar to the Cape of Good Hope and to hand over the letters and papers they have brought with them. All documents are supplied with lead. In the event of a possible encounter with the English, the documents should be thrown overboard so that they will sink quickly and not fall into enemy hands.

If they are unable to reach Table Bay due to the storm - which often rages in that region - there is another refreshment point nearby: Saldanha Bay. An inlet that is still 150 kilometers from Cape Town today. If one of the ships in the fleet is unable to enter Saldanha Bay, it has to go to the Isle of Saint Helena. In that case, the rest of the fleet will sail past the island and signal their arrival with a cannon shot, so that the strayed ship can rejoin the others again.

National Archives in The Hague: 4.VELH [1621/1925], Inventory number 619.35 - Map of Saldanha Bay and Table Bay

Ships from Ceylon will also join the return fleet at the Cape of Good Hope, but if they do not report on time, the fleet will continue their journey to the homeland no later than May 10. Skipper Willem de Vlamingh remains in command of all ships, unless a ship sails with someone with more qualities or a higher rank - which we could not imagine (the VOC authorities add).

If Willem de Vlamingh convenes a meeting with the other skippers from time to time, he will also be the first in rank there. This council will consist of the second skipper of de Gent (Willem van Tessel), the first and second skipper of the Carthago (Servaas Goutswaart and former captain of the Nijptangh, Gerrit Collaert), as well as the sub-merchant Mijndert Vos and all skippers of other ships, such as the Boor and the Santlooper.

Experience shows that on the Company's return ships to the homeland, the ordinary ship's crew - from soldiers to sailors - often experienced great rebellion and tension. Therefore, during the entire voyage, but especially around the Cape of Good Hope, skippers must keep their crew under proper discipline and order, and punish all wrongdoings exemplarily.

The instruction also refers to a treaty with England from 1675. It agreed that all Dutch ships between Norway and Cape Finisterre must be the first to lower their flag when meeting English ships, as a sign of respect. All skippers are requested to do this promptly. The last time a Dutch ship (led by the famous Maarten Tromp) was late with lowering its flag, it became such a riot that it unleashed a real war between England and the Republic!

Followed by instructions for further flag flying and prescribed forms of greetings (with gun salutes). Finally, an order from The Hague from 1680 has been added in which all this is clearly explained. Furthermore, the ships may only enter ports to which they have been sent and the East India Company does not want the skippers to visit each other unnecessarily to party with each other, because that is of no use and is not at the service of the Company.

Now Willem de Vlamingh, as Commanding Officer of the entire return fleet, knows exactly what he has to do and what he must adhere to along the way, the big return journey can begin.

The return journey

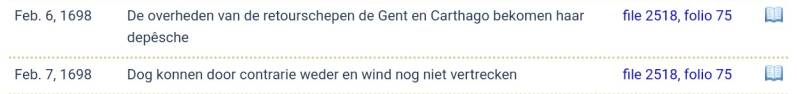

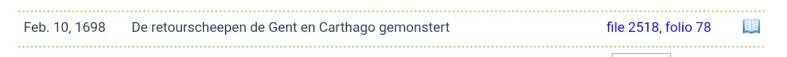

At the beginning of February 1698, the weather in Batavia was so rough and wet that it was difficult to load the return ships (14). It wasn't until February 6 that everything was ready for departure. Thick packages of correspondence were neatly distributed among the various ships at the very last minute. Willem de Vlamingh transported a number of letters with de Gent for the VOC-chambers of Amsterdam, Hoorn and Enkhuizen and also a parcel for Governor Van der Stel at the Cape of Good Hope. That last evening all skippers received the usual farewell meal with the governor.

BRON: ARSIP Nasional Republik Indonesia: Marginalia to the Daily Journals

The intention was to weigh anchor early the next morning, but a tossing and turning west wind and an opposing current made leaving the harbor completely impossible for days. The ships were not mustered until the morning of February 10th.

In addition to the skippers Willem de Vlamingh and Willem van Tessel, the aforementioned sub-merchant Mijndert Vos and two assistants, there were also 99 seafarers, 35 soldiers, 8 impotents and 9 persons without wages on board de Gent. Together it made 156 souls (15).

On Tuesday, February 11, 1698, the ships de Gent and Carthago finally set sail. Other ships, such as the Boor on which Cornelis de Vlamingh stayed, would not follow until later that month and would join them at the Cape of Good Hope to sail together to the Netherlands. This measure of sailing together was mainly to protect against storms and pirates, because the first two ships carried more than 650,000 guilders (16) worth of goods!

In Batavia the high lords constantly kept a close eye on the status of all the ships that had sailed. Almost a week later, the directors received news - via a Chinese merchant - about the return ships de Gent and Carthago which had passed Bantam on the evening of February 13. Another week later they even received a note straight from the Sunda Strait from Willem de Vlamingh, dated February 15, containing no specific content other than a confirmation of her well-being and that they hoped to reach the sea the next day (17).

From April 17 to May 8, the ships stayed in Table Bay at the Cape of Good Hope. There, Governor Simon van der Stel decided on April 22 Willem could also remain in charge of the return fleet for the remainder of the journey. Several ships from Ceylon joined them, such as the Leck, the IJsselmonde and the Berkel, and since the Blois and the Schellach also arrived at the bay on time, they also joined. However, Willem van Tessel remained present as second skipper on de Gent and it was repeated he would take over authority if Willem de Vlamingh died en route.

On Saturday, August 16, 1698, the return fleet arrived in the Netherlands. The big question is whether Willem de Vlamingh was still alive on board at the time or whether he died somewhere along the way?

Read on to the next page for the definitive answer!!

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb