THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE

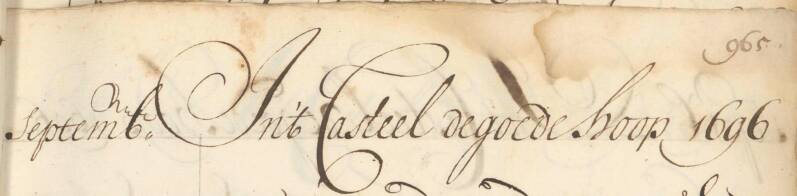

Everything that happened in the bay of the Cape of Good Hope is recorded in the registers of the Castle at this refreshments station. The arrival of the three expedition ships is extensively mentioned in their books.

On Monday, September 3, it is written (1): soo arrived here early in the morning, the Nijptangh. It had 50 Wage-receiving persons on board. On their journey they have lost one man and there are also two sick people who were taken to the hospital here.

On September 7, when the Geelvinck came in, the text reads (2): while the wind was blowing al around, nevertheless commander skipper Willem de Vlamingh with his frigate the Geelvinck, came to anchor with us in the evening. Of the 134 people who recieved salary, he had lost 7 men and brought up 17 sick to our hospital. And almost all the rest of the men on board have scurvy.

Saturday, September 8 (3), there blew a weak southwest wind and towards noon the galliot 't Weseltje eventually showed up here without any deaths or sick among his 14 wage earners. Except for the commanding helmsman, Laurens Zeeman, who had been feeling terribly bad for weeks. (But he made it to the roadstead).

SCURVY

The word scurvy derives from the Latin term scorbut. A common disease on long voyages at sea as result of a vitamin C deficiency.

The symptoms are nasty (but often pass quickly after eating some vitamin C):

- swelling and bleeding of the gums

- bruising (especially on lower legs)

- weakness and tiredness

- stiff and painful limbs

- internal bleeding.

So we can see the ships do not arrive at the same time and it seems there was a considerable amount of deaths to be mourn in the first four months of the journey: seven on the Geelvinck, two on the Nijptangh and, quite soon after arriving at the Cape, Laurens Zeeman also died (the terminally ill skipper of 't Weseltje). Of the entire expedition fleet, that is no less than 10 people out of a total of almost 200 crew members! Well, actually we should write “only” ten, because in those days these quantities were not too bad.

Not long before, on July 27, for example, the commander Hendrik Pronk, mentioned in the previous chapter, had entered the bay at the Cape with ten ships, leaving 188 dead and our Hospital still holding 589 sick. The good man himself was also quite moronic and weak by this time (4). That is why the clerks write about the three expeditioners to the Southland that they were without name-worthy deaths or sick, despite the ten deaths.

New crew

All these sick and deceased crew members had to be replaced. To this end, Willem de Vlamingh went to all hospital wards of the Cape and looked for suitable candidates among the now recovered seamen from ships that had arrived earlier.

There was a problem though, for the commander-in-chief of 't Weseltje had died and Willem could not find anyone at the Cape who knew how to handle a galliot. Therefore the authorities of the VOC did not consider it inappropriate to appoint Cornelis de Vlamingh for this job. It was Willem de Vlamingh himself who asked for this promotion of his son (5).

So, here is what happened: Willem just said he could find no other competent skipper for the galliot and then proposed his own son for the position. The government of the VOC give the position to the young boy and defend their choice by stating Cornelis is a sober and vigilant (= watchful) person who has a lot of experience in navigation. In addition, the VOC members argue it is rather smart to choose Willem de Vlamingh's own son, because they consider it likely that the boy will come to assist his father more faithfully than anyone else in helping him carry out his task. From that the service of the Noble Company can only benefit (6).

With this promotion, Willem de Vlamingh let his son (who is only 18-year-old at the time) skip a number of steps on the ladder of steermanship. After all, the boy was only third watch on the Geelvinck and would first have to practice both the role of second mate and chief mate before he could become skipper. With this appointment they went right against all regulations of the VOC. Since 1661 there had been a law to ensure someone always first had to be chief mate before they could become a skipper. Willem de Vlamingh clearly did not care about all of this. In retrospect it appears to be in the same year of the appointment of Cornelis (in 1697) that a new law was passed in Batavia, which stated no second mate could be promoted to first mate without an examination before a committee of two skippers and an equipage master (7). Perhaps this new rule wa adopted partly because of this appointment of Cornelis by his father?!

Portrait of Victor Victorszoon, by Tako Hajo Jelgersma, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1940-337

On the advice of Nicolaes Witsen, in the Cape a painter went on board of the Geelvinck to make pictures of the new land.

The mayor of Amsterdam originally even ordered two painters to go along with the trip, but only one of them actually went. Commander Hendrik Pronk had a corporal on board who understood the art of drawing and who should have been disembarked at the Cape of Good Hope to sail with the expedition. But Pronk's ship, which had departed more than four months before the Vlamingh, had of course already sailed on, corporal and all, by the time Governor Van der Stel in Cape Town received this assignment.

In the end, a man called Victor Victorszoon boarded on the Geelvinck and made beautiful watercolors of all the coasts he saw along the way.

New supplies

At the Cape, all kinds of provisions and goods were first stocked before departure. We know this from all the receipts that have been preserved (8). On it we read, among other things, for the Geelvinck a supply of 12 raw ox hides, 4 firs, plus, for example, paint and three colors of flag cloth (red, white and blue). 48 sheep and 14 cattle also went on board. At the smithy they bought iron, steel, copper and tin (probably the tin they used to make the dish that has now become world famous).

Furthermore, of course, the necessary quantities of rice, wheat flour, salt and sugar, plus as much fresh vegetables, herbs and wine as possible. On October 25, 1696 Willem de Vlamingh signed for receiving all these goods at the castle in the Cape and just above his signature you can see how a large batch of tobacco (tabak in Dutch) was added to the shopping list at the last minute.

See the National Archives in The Hague, about the VOC 1.04.02, Overgekomen brieven 4037, pages 1449-1452, (= scan 717)

Somewhere in these lists of goods is also the purchase of a number of items of clothing bought especially for 3 Indians (10). Willem de Vlamingh had taken three black chain-goers on board as interpreters, experienced in various languages. So three enslaved people went with the expedition members on this trip, whom we fortunately know by name: Aje van Clompong, Mangadua van Macassar and Jongman van Balij. These "interpreters" not only spoke Malay, Javanese, Portuguese and German, but also all kinds of languages unknown to us, such as Lampoenders and Biema (11), which are actually all Indonesian dialects and which of course were of no use to them in the Southland. The company gave these three men a completely new wardrobe. For example, for each of them is a pair of shoes and a suit with brass buttons mentioned on the scroll. The shirts they received cost as much as the tobacco they were allocated for the journey (12). After their task was completed, these people were probably promised to regain their freedom as a form of "wages".

The languages one of these forced interpreters - called Aje from Clompong - would be able to speak (mostly Indonesian dialects)

All in all, it took seven weeks for the expedition members to leave the Cape of Good Hope on October 27, 1696, while the period at this refresh station usually took three to four weeks. Later, this long “resting period” of Willem de Vlamingh will be strongly resented by Nicolaes Witsen, as if the skipper had entertained himself with parties, gambling and women and had been drunk all day. In our opinion, this is a very unfair accusation!

Fraud on the Nijptangh?

During their stay at the Cape, the skipper of the Nijptangh got in trouble (13).

A man named Joan Blesius - who was the independent fiscal of the VOC - writes an urgent letter from the castle at the Cape to the government of the East Indian Compagny in Amsterdam. This officer tells the board of the VOC that with the arrival of the Geelvinck, Nijptangh and 't Weseltje, a new instruction was also handed to him. Apparently the rules changed quite often.

Mister Blesius discovered skipper Gerrit Collaert of the Nijptangh had not followed the instructions in all aspects as he should. For example, he regularly gave his crew members only half their rations of brandy, butter and meat. As a result, the skipper of the Nijptangh was left with no less than 18 jugs of brandy and a whole lot of meat. There were 5 barrels of meat on the list with supplies when he left Holland, but he only emptied 3 barrels with necks and bones between Texel and the Cape. These last three barrels were not on the ship's list, which made everything even more suspicious. As punishment, they withold three months' wages of Gerrit Collaert.

Proceedings

Another skipper, who also had a lot of food left (meant to feed his men during the voyage) and who demonstrably tried to sell them, was punished even more severely. The letter even lists a long line of skippers and bookkeepers who, in the eyes of this Cape klerk, have not adhered to the new rules well enough and all of whom this mister Blesius has brought before the council to be punished with the deduction of a few months' wages!

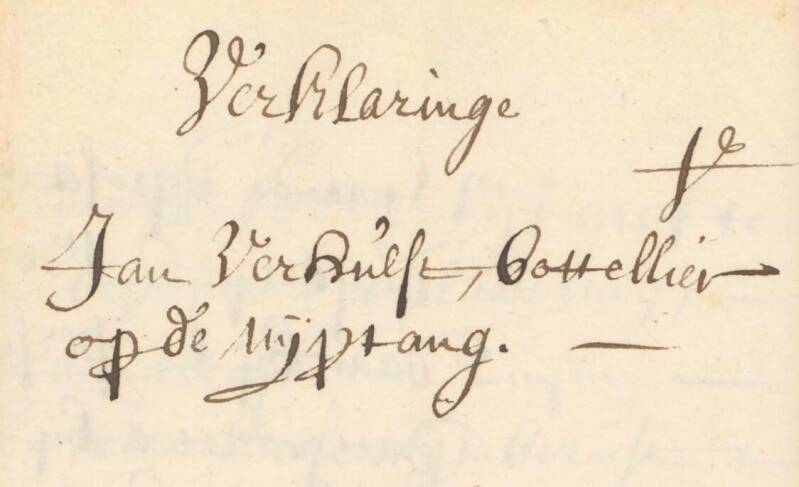

Statement from the bottler

Yet in the case of the Nijptangh something really seems to have been going on. This became apparent when the bottler of the Nijptangh, Jan Verhulst, had to appear as a witness in the above mentioned case about the left over meat before the Council of Justice at the Cape. He stated there were indeed five barrels of meat and three barrels of "necks and bones" on board the Nijptangh when they left the homeland.

According to the bottler, he acted on behalf of skipper Gerrit Collaert and distributed the meat so that every man only enjoyed half an ll (14) of meat. As a result, on arrival at the Cape roadstead, the third barrel of bones was still open and the five barrels of meat were still untouched in the hold.

This declaration was signed in December 1696, when the expedition members had already moved on, but the bottler had not traveled with them to the Southland.

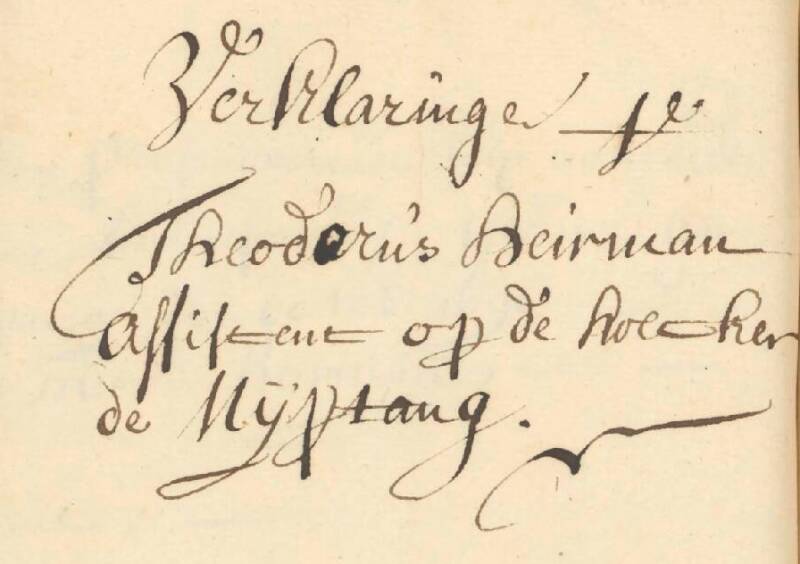

The bookkeeper of the Nijptangh, Theodorus Heirmans, also had to appear before the council in connection with this problem. He claims not to know what goods were in the hold during the voyage. The bookkeeper says he has never been given the true knowledge of this by skipper Gerrit Collaert, while as bookkeeper he himself is of course responsible for having his affairs in order.

Declaration of the assistant (bookkeeper)

In addition, the bookkeeper declares: I have also seen on the voyage that the same skipper has tapped brandies of the Compagny so now and then. He filled twelve bottles with them and mixed them with his own private brandies. so Gerrit Collaert siphoned brandy intended for his crew into bottles for his own use.

Then the same ship's bookkeeper confesses something else to the council, just like that, without anyone asking him. He tells them skipper Collaert offered him to split the momey (hundred reales of eights he received from the company). Apparently the skipper of the Nijptangh proposed to share the money they had obtained from the VOC. And according to the bookkeeper's statement Gerrit Collaert wanted the largest part of it himself. To which the witness said he did not need any money and that is why this shady transaction did not take place. On the day of departure (October 27) Theodorus Heirmans confirms and signs his statement, but gets on board with Gerrit Collaert anyway and travels with him to the Southland.

Interrogation of the boatswain, the constable and again the bottler

The council wants to get to the bottom of the matter and therefore interrogates not only the boatswain, the first mate and the constapel of the Nijptangh, but they also want to speak to the bottler Jan Verhulst again. All under oath, because at least one of them always was present at the weighing and distributing of the rations to the people on board. They claim things have always been orderly and all crew members enjoyed their rations of food and drink: a sip of Spanish wine three days a week, and a drop of brandy every morning on the other four days (which is about a quarter of brandy for every man).

However, the answer on question number 4 shows none of them were present when the bottler tapped the rations of drink. To which the bottler indicates he never went to the hold himself to drain the rations, that was done by the skipper or the mate.

On October 11, 1696 skipper Gerrit Collaert and bookkeeper Theodorus Heirmans face independent Joan Blesius before a plenary council, in which not only all members but also the governor himself are present. Joan Blesius has thoroughly inquired whether the men had properly complied with the instructions given. In his view, that is not the case: they have never observed Articles 4, 5 and 6.

The bookkeeper is accused of not keeping a consumption book during the journey from the homeland to the Cape. Not even the slightest note. Gerrit Collaert, who had the highest authority as skipper, did not hesitate to give his men only a quarter of brandy, while the ration letter (with new instructions he received) expressly dictated that the crew should each receive half every day, so the double amount!

Another conclusion was that the skipper should also have known from his ship's list there were 5 barrels of meat on board, and yet he only gave his men from the three barrels with necks and bones. So on arrival at the Cape there were still 18 jugs of brandy and a huge cargo of meat left. Of course the VOC suspected the skipper intended to sell all of it for a lot of money. The inspector therefore cannot help but conclude this is a dirty and fraudulent trade.

Signature of Joan Blesius

Well well, this is quite the portret of skipper Gerrit Collaert and until now we have never read anything about his misbehaviour anywhere!

Manslaughter

A lot of interesting things happened during their stay at the Cape. All in all, the three ships spent seven weeks in the bay of the refreshment station. A number of facts stand out when we leaf through the daily records kept at the Cape during that period (15).

Firstly, it immediately becomes clear how incredibly important the weather report was for all sailors. Almost every day the book klerks start with a report on the local weather conditions. For example, in the afternoon of Monday September 10 (when the three expedition ships have just been reunited in the bay) we read there was thunder and lightning. The storm increased considerably during the next hours and did not subside until later in the evening. A lot of rain seems to have fallen in this period, because all plants in the lowlands were drowned by the floods.

We keep talking about the castle of Good Hope, but to be honest, this building looked more like a fortress. Just take a look at this sketch of it by Isaak de Graaf from 1674. National Archives The Hague

In addition to all the information about local climate, we also read about a certain Jan van Es, who was suspected of manslaughter. This sailor drank too much and played a game of dice with the other men of the ship the Soldaat. An argument arose and knives were drawn. Jan's opponent died, but he only confessed his deed after being tortured several times with iron chains. A few days later Jan van Es was sentenced to death and on October 6 (while our expedition members were still in the bay) he was executed.

In between all these reports, we occasionally find some small messages about our three expeditioners. On Thursday, September 13, we learn the three ships were given fresh bread for 8 days by order of the governor of the Cape. And on October 4 it says they are busy providing the three ships destined for the Southland with all the necessary food and drink.

On October 16, people at the Cape think they see the ship the Berkel on the horizon. The ship fires a shot within sight of the port, because they are in distress and request assistance. The next day it turns out it was not the Berkel but another Dutch ship called Vosmeer. Yet, it may very well be someone did recognize the Berkel the day before, because they also tried - according to their own logbook - to enter the roadstead on the sixteenth of October and failed as well because of the bad weather. They turned around and took shelter in a bay further on (the Saldanha Bay) only to arrive at the Cape of Good Hope on 23 October.

This concerns the same Berkel, which departed from Texel on 3 May together with our expedition vessels and stayed in their neighborhood for almost a month. However, the sailors on the Berkel had a lot of bad luck on board. Among other things, their watermaker was ill from the start and eventually died. His assistant turned out to have absolutely no knowledge of making water! So they had to enter a refreshment station long before they reached the Cape and entered the roadstead at the Cape Verde Islands to stock up on fresh water (16). They also seem to have gone off course from time to time - the log regularly states in the margin they are further north or south than they had estimated. Perhaps it shows Willem de Vlamingh's skipper skills for him to reach the Cape so much earlier? Or maybe skipper Leendert van Deijl of the Berkel just had back luck with the weather and his equipment.

The margin of de Berkel's logbook states that on September 16 they were 36 minutes further south than they had guessed

One of the many cases of material breakdown on board the Berkel. This happend on August 6, 1696

On July 21, they were 21 minutes further north than they thought, according to this note in de margin

A lot can happen along the way. On the same October 17 (the day after the storm that prevented several ships from entering the harbor), the Dutch ship 't Huis te Duijnen also arrives at the Cape of Good Hope. They counted no less than 93 dead and the rest of the crew of 236 members feels sick and weak, except for 4 men! The (English) captain only had one sail left. To sail properly he needed at least three! So he wants to buy two sails at the Cape. Initially his request is rejected by the VOC. After much insistence from the skipper, the governor finally sells him two old sails from a previously stranded ship. They have been eaten by rats and therefore had no real value anymore. Still the poor captain had to pay almost four hundred guilders for these sails. All this paints a picture of the grimm world in which Willem de Vlamingh operated.

The profession of skipper was apparently a tough one and the crew was also not always treated with gentleness. For example, because of mutiny on the English ship the Mary, one of the delinquents aboard of that ship was sentenced to death (and strangled with a rope a few days later).

We found a most remarkable entry on Monday 22 October (our expedition members are still in the bay). That morning 8 company officers and 6 chained men were missing, and also 2 more men from the frigate the Geelvinck. No less than 16 people went awol that particular morning, including - as we saw much to our surprise - two crew members of Willem de Vlamingh's ship!!

All these people deserted from the several ships lying on the roadstead. A look at the books of the Geelvinck shows indeed two crew members took of at the Cape (17).

See the National Archives in The Hague, at the VOC: 1.04.02, inventory number: 5435

It concerns two Germans: Jan Dirx van Bos from Diez and Jan Eijens from Norden. One had the function of gunner and the other was a boatswain, so he was someone who is in charge of some of the sailors. We know this boatswain already had many debts before leaving the Netherlands: there was an I Owe You of 150 guilders in his name (probably borrowed money) and he still had to hand in 3 months' wages due to some sort of Condamnation (apparently he had been convicted of a minor offence). In addition, he still had to pay the company for a large part of his gear, such as a pair of shoes, stockings, shirts and one woolen plus two linen suits. All in all, he owed more than 200 guilders to several people, while he only earned ten guilders a month.

We do not think one of these deserters have ever been found again, because they are permanently deleted out of the books of the VOC on October 26 (the day before departure of our three ships) and we do not encounter them elsewhere anymore.

Midshipman Johannes Scherenberg from Oldenborg also disembarks from the Geelvinck. He is taken to Land by order of the governor of the Cape of Good Hope. It is not stated why (18).

A few days before departure (19) the government of the Cape gave a package with letters to the captain of the English return ship Mary for the noble gentlemen of the VOC in Amsterdam and they also gave a double set of letters to Willem de Vlamingh, which he must hand over to the high government in Batavia as soon as he arrives there. Apparently the expedition members are finally about to leave.

Picture of Table Top Mountain taken by Jan Houter

The next day it says (in the books of the VOC) everyone is busy arranging further supplies for the ships heading towards the Southland and they are ready ti set sail, which means our expedition members are indeed preparing for departure. The men on board will be mustered the next day. We are curious if they mannaged to replace the two deserted crew members at the last moment or whether the Geelvinck left with two fewer men.

On Saturday, October 27, the time has come and the registers state Willem de Vlamingh had everything he needed for his further journey. As the Geelvinck leaves the roadstead in the company of the Nijptangh and 't Weseltje, the clerks write them a blessing and ask the Almighty to grant his blessing on the voyage. Although ships sail from the Cape every day, we rarely see an administrator giving one of them a blessing, like is happening here. Of course, the VOC hopes Willem will return with favorable news for the compagny.

Expectations were high all around. This is also evident from the fact that the expedition members made the newspapers in the Netherlands. The Oprechte Haerlemse Courant of 4 July 1697 tells the story of a Danish ship - which had arrived in Denmark from the East Indies on 30 January - had brought letters from Caep de Bon Esperance. These letters contained news of various Dutch ships that had left the homeland for the East Indies last year and passed the Cape in good condition, among them was Skipper de Vlaming with the ships going to the Southland. In this way, the home front was kept informed of the expedition's progress, although they did not hear about it until eight months later.

See the last sentence of this newspaper article in the Oprechte Haerlemsche courant, July 4, 1679 (found via Delpher)

Busy roadstead at Table Top Mountain. This is an image Willem de Vlamingh will be very familiar with.

VOC return ship 'd Gerechtheid' on arrival at the Cape Colony circa 1744, painted by the marvellous Dutch autodidact Arnold de Lange, oil on panel, 30x40cm (beautiful paintings, all for sale on his website)

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb