CORNELIS

What role did he play in a bribery case?

Cornelis de Vlamingh accompanied his father on the expedition to the Southland and eventually even became one of the three skippers on this adventurous voyage. In our opinion, father and son should have been united together in a statue on Vlieland or in Australia. Instead, we are now erecting an online monument to Cornelis by describing his life.

Career

As soon as Willem de Vlamingh was appointed as a skipper at the VOC, he took his son along on his trips. Cornelis was only ten years old at the time and, as the youngest servant, he performed all kinds of jobs on board for which he was paid only 8 guilders a month.

In 1688 Cornelis earned 8 guilders a month as an errand boy (National Archives in The Hague: 1.04.02, 5360)

It seems from the age of fourteen Cornelis was sent on ships other than the one on which his father was skipper. For example, Cornelis Vlamingh van Vlielant sailed from March 1692 on various ships with cool names such as the Batavia, the Java and the Bantam (1). The latter left Java on December 7, 1693 and arrived in the Netherlands on July 27, 1694, while Willem de Vlamingh himself had left the Texel roadstead on January 7, 1694 as skipper on the Meerestein.

It was not until their great expedition to the unknown Southland that Cornelis - who had since risen to the rank of third guard - served again under his father on the Geelvinck. During the trip, Cornelis was promoted to the rank of commanding helmsman of 't Weseltje (and thus skipped two whole ranks). After their great expedition, Cornelis made several more voyages as a skipper for the VOC. On his last journey, he was appointed commander of the complete return fleet - just like his father once was. Quite an honor! As we shall see, he got a golden medal for it.

The voyages of Cornelis de Vlamingh as skipper (2)

Huis te Bijweg

Stad Keulen

Nigtevecht

A brand new ship that was built in 1699 (3). On May 9, 1699 it departed from Texel with 50 men and on January 28, 1700 the ship arrived in Batavia.

December 2, 1700 departure from Batavia, July 18, 1701 arrival at the Texel roadstead. In the meantime, Cornelis is staying on Vlieland (4).

April 28, 1703 departure from Texel, December 9, 1703 arrival in Batavia (5).

Sailed as skipper on the Nigtvecht until June 27, 1704.

Huis te Dieren

Bengalen

Limburgh

Koning Carel

Berbices

From July 1704 (6) to Aug 1706.

From January 1, 1707 to October 1713.

November 26, 1713 to February 4, 1714.

From February to approximately July 17 (5 months in total).

Skipper from August 1714. In this position Cornelis de Vlamingh was elected commander of the return fleet (7). An honor his father also received more than 15 years earlier. On November 26, 1714, the Berbices left Batavia with several ships and on August 6, 1715 they arrived at the Texel roadstead (8).

In Batavia

Not long after the expedition to the Southland, Cornelis married Constantia Soreau (9), who was six years younger. She came from a well-to-do Amsterdam family (10). Together they left for Batavia where they started a family. They lived there for several years. We know this from the will Constantia had drawn up at the end of her life (11). That day she came to the notary alone. 54-year-old Cornelis was still alive at the time, but she was unable to get him to come to the law firm. Although she had tried to persuade her husband several times, also in the presence of good friends, to come with her for quite some time, Cornelis permanently refused. In his eyes, it was enough they had once drawn up a joint will.

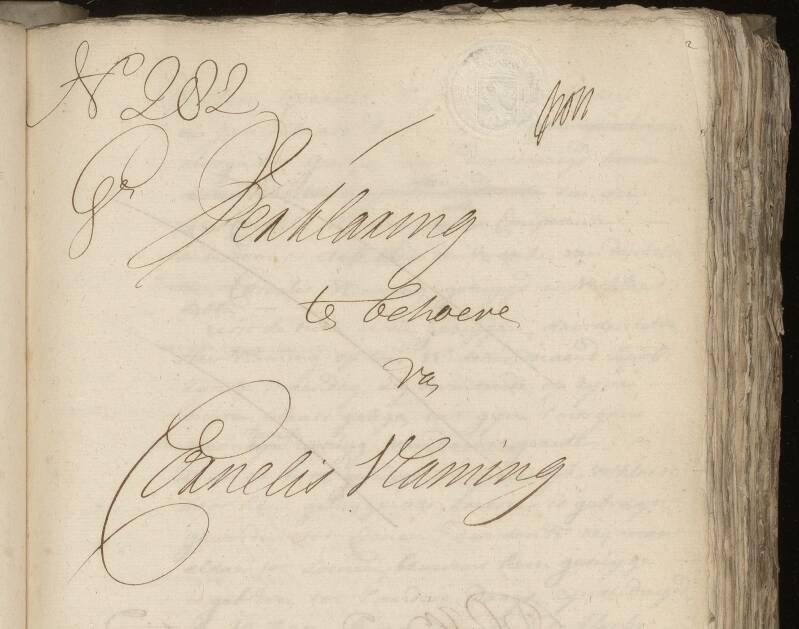

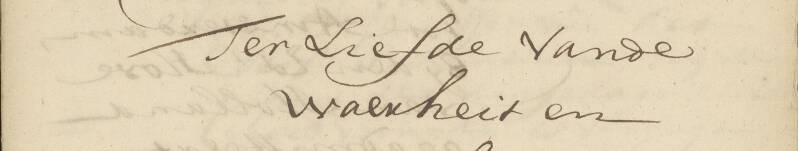

Image of a book especially made for the wedding of Constantia's grandparents

This first so-called “mutual will” was drawn up 25 years earlier on Batavia (12). Shortly after signing their testament, Cornelis went on a trip again for work, while Constantia gave birth to their first child. When Constantia became ill soon afterwards, she also had a codicil drawn up on August 27, 1705, in order to make sure everything was arranged properly for her child in the case she died of that illness while her husband had not yet returned. .

So the sick Constantia was far from her family when she gave birth to a baby while her husband was at sea. She recovered herself, but the baby did not survive. And then follows the heartbreaking announcement that they have had several children, but these childeren - like their firstborn - all died at a young age a long time ago. The couple continued their life without the childeren they longed for.

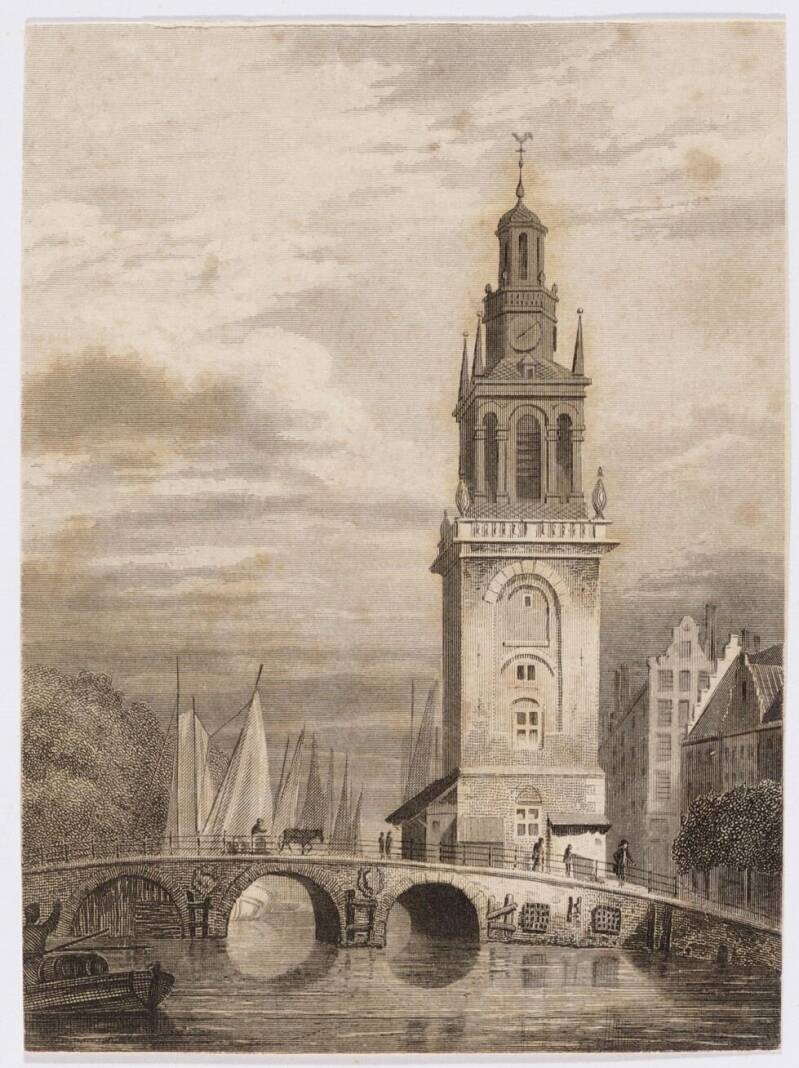

After living in Batavia for a number of years, Cornelis and Constantia returned to the Netherlands and settled in the capital. First on the Singel near the Jan Rodenpoorttoren, which stood on the corner of the Torensteeg. In1725 they moved to the other side of the Raadhuisstraat, to a house about 500 meters away, directly opposite the Utrecht ferry boats. Cornelis and his wife saw every day how these cargo ships - because that's what they were - sailed back and forth to Utrecht

These are the boats Cornelis and Constantia saw from their window (Collection Rijksmuseum)

The couple very regularly acted as witnesses at the baptisms of various nephews and nieces on both her and his family side (13). Being a godmother or -father was not only a great honor, it also came with a huge responsibility. If something happened to the parents of the baptized child, they promised to take over the care of the orphaned child. The many godparentships Cornelis and Constantia were entrusted with says a lot about them as the people that they were.

In Batavia they also took care of no fewer than four children from Constantia's side of the family for a number of years and had them under their supervision, management and education (14). Once again we see family members who take good care of each other.

Two amusing stories

In the archives we found two nice anecdotes about Cornelis which we would like to share. For example, from one of his many trips, he once tried to send a beautiful box to his eldest sister Evertje in Amsterdam (15). To this end, he gave the box to a skipper in Bengal who happened to be sailing to the Netherlands and told his sister in a letter where she could pick up the trinket in question.

So, after receiving the letter, Evertje reported to skipper Dirk van der Weijde, who was staying in the city at the guest house Het Turfschip van Breda. She asked him about the box with the marks A.V.S. full of goods that this skipper in Bengal had received from Cornelis to give to Evertje. However, the skipper claimed he had the package delivered to the Oostindisch huijs and that she could pick it up there. Regrettably, no matter how hard the VOC building was searched, the mysterious box was nowhere to be found.

Evertje suspected the skipper had kept the package for himself, because an acquaintance of Evertje who was on board with Dirk van der Weijde had offered the skipper to take the box to Evertje, but the skipper claimed he would do it himself. When Evertje's acquaintance later arrived in Amsterdam, he checked the list and the box in question was no longer listed among the goods... We can only guess at the contents. It never surfaced again.

Statement on behalf of Cornelis de Vlamingh

We are presented with a similar mysterious story on the day Cornelis de Vlamingh dragged both his gardener and his maid to a notary's office in Amsterdam (16). He had the gardener testify that he, Cornelis, was simply staying at his estate at the Gein (where the family had a country house) on Monday, September 11. That morning, the gardener said he personally brought Cornelis as a coachman to Loenen in a carriage. The two men stayed there until five o'clock in the afternoon the next day. The story does not tell what they did in Loenen, but at seven o'clock in the evening they eventually returned to the country estate where they slept. The next day Cornelis drove to Amsterdam, also in a carriage.

Why those exact day indications were so important becomes clear later in the deed when the maid Giertje speaks. She stated she was looking after the other de Vlamingh family's house in Amsterdam by herself. On Tuesday morning a certain paper or writing was delivered there. She then told the person who brought it the master of the house was in the country estate and she did not know when he would return to the city. Whereupon the person left the paper and went away.

The next day Giertje prepared the note to send it to the country estate via the Geijnse Schuijt (a mail boat), when Cornelis suddenly arrived in Amsterdam. The girl then personally handed the note to Cornelis and now solemnly declares her Lord did not know any earlier than that moment about the paper which was brought.

Map of Gerrit Drogenham around 1700 and zoomed in on the piece at the top right with the name Juffr. Van Gelder (the previous occupant of the country estate of Cornelis)

Why was it so important no fewer than two servants testified for Cornelis that he was only aware of the message on September 13 and really not a day earlier? We can only speculate about this, but it was probably - as so often - something about money.

What's so nice about the above-mentioned country estate on the Gein is its name: Oost-Vlieland! On April 25, 1722, Cornelis and his wife bought this large estate from one Anna van Gelder for 10,500 guilders (17). In addition to a mansion and a farmhouse, it also included approximately 29 hectares of land (more than 15 football fields in size) where they kept oxen, cows, horses and a pig. So somewhere in North Holland between Weesp and Abcoude there was a piece of land on the east side of the Gein called Oost-Vlieland! (18)

And a less nice story

Read here about the sad life of Constantia Soreau's youngest sister

Seedy business

Cornelis was only 37 years old when he stopped sailing. He seemed to have found another source of income in Batavia and during his years as a skipper in the service of the VOC: bonds. We have come across more than a hundred deeds in which he lent people money at a certain interest rate. These were often seafarers who got a job on a ship by mediation of Cornelis and paid a large sum of money in return. And even though Cornelis seems to be just an intermediary who worked for a certain Willem Sautijn, this case haunts the De Vlamingh family to this day and that is why it makes sense to pay some attention to it.

Newspaper article from 1931

Job trading was prohibited at the time, but was still a fairly common phenomenon. However, as director of the East India Company of Amsterdam, Colonel Sautijn went way too far (19). He wanted to see money even for low-level job appointments. He also lent people the necessary amounts of money at a sky-high interest rate of no less than 10%. Colonel Sautijn earned around 23,000 guilders from the sale of positions alone in a few years.

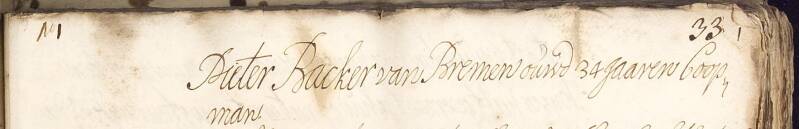

The case came to a head when his accomplice Pieter Backer - a run-down German from Bremen - suddenly insulted a woman at a fancy party of Colonel Sautijn. One of the other guests offered Sautijn a choice: get that Backer out or I'm leaving. Pieter Backer then had to leave immediately and vowed revenge.

Biographical dictionary with information about Willem Sautijn

The humiliated accomplice went to the police in April 1724 and told them a lot about the colonel's fraudulent practices, but he could not prove anything. The chief sheriff did not dare to take on the influential Sautijn family (Willem's brother, Nicolaes Sautijn, was mayor of Amsterdam at the time). In the end Pieter Backer himself was convicted by the aldermen on December 14 and Mr. Sautijn went free. Backer had to pay a 6,000 guilder fine and was not allowed to enter Amsterdam for four years.

Under pressure from public opinion, they ultimately did not leave it at that and the court then heard several witnesses, including Cornelis, but he did not say a word. Afterwards, he and his wife presented themselves to a notary to make a declaration for the love of truth (20). It turned out skipper de Vlamingh, just before he had to appear before the committee of the provincial court, was pressured by Colonel Sautijn not to answer any questions, otherwise his sister might have been harmed.

For the love of truth

Apparently Cornelis could harm his eldest sister Evertje by his testimony and this is why he tried to keep his mouth shut that afternoon in front of the court at the Doelen in Amsterdam. But the committee members did not accept this, which meant Cornelis ultimately had to answer all the questions. He did this with a heavy heart and many emotions. After all, he is a sailor and has no understanding of lawsuits, he argued in his defense. Once he got home, Cornelis realized he had not explained himself clearly to the committee and this is why he is now at the notary to relieve his burden and to explain the matter in more detail in all honesty.

Start of the process. (From the Archives of Sheriff and Aldermen)

Ultimately, his sister Evertje Vlaming was also heard in court in this case (21). Evertje freely admitted that she had sold a total of three skipper's jobs for Sautijn in the years 1719 and 1721, each for an amount of approximately 2,000 guilders (22). That is of course a lot of money, but it seems more like Evertje has been a middleman three times than a seasoned accomplice of a notorious criminal. Especially because Evertje probably should have simply given most of that money to Sautijn, although she would of course have received compensation for her role as an intermediary.

According to the Algemeen Dagblad of two centuries later (1931), the statements of the witnesses were ultimately crushing for Sautijn, especially that of Evertje Vlaming!

Her openness was the deciding factor in convicting the colonel. However, the case was dragged out and before the Court of Holland could pass judgment, Willem Sautijn died on November 10, 1731.

Last days

And then suddenly Cornelis' wife, Constantia, died on August 23, 1734 (23). She had just turned fifty two months earlier.

Her passing was probably quite unexpected, because four days earlier Cornelis bought a house at Treeftsteegje (24). This building was less than a hundred meters from their home in Amsterdam and was intended to serve as a stable and coach house at their home (25). Cornelis' signature under the deed of sale is noticeably wobbly. Could he have suspected something or were they both sick?

Signature of Cornelis de Vlamingh

A busy period began for Cornelis de Vlamingh. First Constantia had to be buried. This happened in Amsterdam, the city where she was born and had lived all her life. The church book states for August 27:

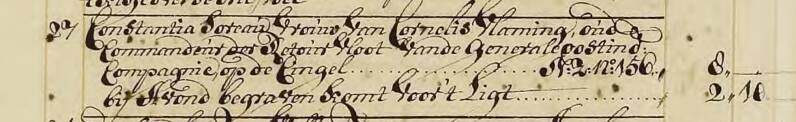

Constantia Soreau, wife of Cornelis Vlaming, out Commander of the Return Fleet of the General East India Company, on the Cingel. (8 guilders). Burial at Evening Comes Before Light (2.10)

Cornelis' wife died in their house on the Singel, where they lived together for more than ten years. The funeral cost 8 guilders. Because she was buried in the evening, there were some additional costs for the light. Since daylight saving time was not yet practiced in those days, the sun set around the end of August at half past seven. At the time, it was considered extremely chic to bury the deceased in the evening.

Grave number 156 in the old church in Amsterdam

Constantia probably received her final resting place in the Oude Kerk, behind gravestone number 156, in the eleventh layer on the north side of the church. Cornelis was half the owner of that grave (26).

After the funeral, Cornelis had a bussy time carrying out Constantia's last will. Some items had been assigned specifically to someone by her, from her gold watch and diamond ring to an expensive church book and silver tea kettle. She wanted her clothes divided among her nieces. In addition, Cornelis had to hand over all his wife's jewelry. These jewelry were sold at her request and the proceeds went to the Amsterdam Orphanage. Their maid, Joanna of Macassar, should of course not be forgotten. This East Indian Domesticq had probably come with them from Batavia when they moved back to the Netherlands and Constantia expressly asked her husband to remember to give her a nice annual sum for the rest of her life.

The Oude Kerk, seen from the other side of the Oudezijds Voorburgwal. From: 's Waerelts Koopslot, 1723, Jacobus Verheyden. Image bank Amsterdam City Archives

Cornelis worked himself to death. Especially because Constantia had stated in her will he had to provide a complete inventory of both their estates within six weeks, which was a huge job. But as a result, we now have more than 32 pages of insight into their material possessions (27). Anyone who leafs through it will see that the entire house is full of things from the East Indies, brought with them in the year 1715, such as a Bengali kris, a Javanese sofa and countless pieces of Japanese tableware for tea, coffee and chocolate milk. And who has almost 300 napkins?

The most striking is a cabinet especially for all silverware. This was placed in the most visible place in the living room and in it the family members appear to store their most important things in addition to the silver cutlery. Cornelis kept his tobacco container in it with a spittoon (a container in which he could spit out the juice of his chewing tobacco) and Constantia, among other things, her powder box, pin box and thimble. But our eye is especially drawn to two very special items:

Two valuable chains in the inventory of Cornelis de Vlamingh (Amsterdam City Archives, Notarial Archives number 5075, Inventory number 9754, scan number 361)

The first object is a silver chain worth 256 guilders and 10 stuivers, of which it is added in the margin that it was honored by the directors of the VOC when Cornelis fought against French warships in 1702. We didn't know anything about that!! Via Delpher we looked through all the newspapers from 1702 and, to our great pleasure, found a long piece in the Amsterdam Courant of September 2, 1702, so we can now read everything about this dangerous episode in the life of Cornelis de Vlamingh:

Found via Delpher.nl

Transcription in Dutch:

De commandeur Cornelis Vlaming, met het fregat van d’Ed. Geoctroyeerden O.I.Comp. uytgeweest zynde om te kruyssen, heeft op den 22 Augusty omtrent Hitland (dat zijn de Shetland Islands)gesien 5 Fransche Konings oorlogschepen, die hy eerst voor schepen van de Compagnie aensag; en het eerste, een schip van 52 stukken (kanonnen) genaderd zynde, geraekte hy met het selve in een gevegt, ‘t welk omtrent 4 glasen (= twee uur) duurde, geduurende welk gevegt de voorsz. (voorszegde) Commandeur, hoewel sijn Fregat maer 26 stukken voerde, het vyandlyke schip soo veele schooten onder water toebragt, dat hetselve in onmagt lag, en daerna gaf hy het nog een laeg, waerdoor de fokkemast en steng over boord viel, wanneer het Fransch schip ook een groot gat in de boeg hadde, ‘t welk by ‘t slingeren van ‘t selve, water schepte, waerdoor een groot misbaer onder de Franschen ontstond. Dit geschied zynde quamen 2 andere Fransche oorlogschepen dit ontredderde schip te hulp; en de Commandeur Vlaming alleen zynde, vond goet om sig doenmaels af te wyken (hij maakte zich wijselijk uit de voeten); waerna hy bevond dat hy maer 7 dooden en 13 gequetsten hadde bekomen; dog dat sijn zeylen, raes en want, seer waren beschadigt. Den 24(-ste) wanneer de voorsz. Commandeur weder nae sijn bescheyde plaets wilde zeylen, wierd hy weder van 2 Fransche oorlogschepen gevolgt, ‘t welk hem dede resolveeren (besluiten) om na Tessel te keren, alwaer hy gisteren gearriveerd is.

Loose translation in English:

On August 22, Commander Cornelis Vlaming, cruising with a VOC frigate, saw 5 French King's warships around Hitland (that is the Shetland Islands), which he first mistook for ships of the Company; and having approached the first, a ship of 52 cannons, he got into a battle with it, which lasted about two hours, during the battle Commander Vlaming, whose frigate carried only 26 pieces, dealt the enemy ship so many shots under water that it was out of power, and then he gave it another shot, causing the foremast and stem to fall overboard, then the French ship also had a large hole in the bow, which created water when it swayed, causing a great commotion among the French. This happened when 2 other French warships came to the aid of this devastated ship; and Commander Vlaming being alone, he wisely got away; after which he found out he had only received 7 deaths and 13 injured; but his sails and rigging were damaged. On the 24th when Commander Vlaming wanted to sail to the same place again, he was again followed by 2 French warships, which made him decide to return to Texel, where he arrived yesterday.

The second item in the silver cabinet mentioned on the contents list is even more valuable, judging by the price: it is a chain with a medal, worth a total of 399 guilders. This also turns out to be a gift from the directors of the VOC to Cornelis, because he returned home in 1715 as admiral of the fleet. Because just like his father, Cornelis was commander-in-chief of the large return fleet from the East and we wonder whether Willem de Vlamingh ever received such a medal aswell?!

Finally, we will mention just a few telling items elsewhere in the house from that enormous inventory: for example, the couple kept an empty parrot cage at the top of the attic, as well as a chest with 20 cotton children's shirts and a doll set. Their two portraits, worth 15 guilders each, stood prominently on the mantelpiece. And in the end, Cornelis - who has been ashore for years - turns out to have never forgotten the sea, because he owned shares in many ships. Most of these were fluyts that regularly went to Greenland for whaling!

Cornelis invested in several ships with names such as the Juffrouw Maria, the Constantia, the Young Cornelis and 's Lands Welvaren (Amsterdam City Archives, 5075, Inventory number 9754, scan number 373 and 374)

Jan Roodenpoortstoren from 1852, seen from the bridge for the Warmoesgracht in a northerly direction to Torensluis. On the right the houses of Singel 159-161 (Image bank Amsterdam city archives)

Two months after the death of his wife and still in the middle of everything he had to arrange for her last will, Cornelis decided to draw up his own testament. On October 23, 1734 at eleven o'clock in the morning, Cornelis Vlaming had a notary come to his home (28). His eldest sister Evertje's daughter was also there and immediately after Cornelis at half past eleven it was her turn to draw up her will (as if they supported each other in this difficult job).

What were Cornelis' wishes? First he left all the furniture, household effects, gold, silver, jewels and trinkets to his eldest sister Evertje. Only the large gold chain with the medal on it (which he received as a tribute after sailing as admiral on the return fleet) went to his cousin Arend Selkart. Just like all his clothes. So this medal was a special heirloom that the whole family was proud of!

Cornelis left Evertje's daughter an amount of 34,000 guilder, from which she could earn interest throughout her life. A huge amount! And he also remembers his wife's wish to give their old maid a good annual allowance.

In the months after Constantia's death, Cornelis appeared no fewer than 14 times in the office of Son's notary regarding the handling of his wife's last will. This whole affair probably deeply affected the old sailor, who was now left alone. Because while the very last things were completed on December 13, Cornelis himself died not long afterwards - on January 18, 1735 - just five months after his wife.

Remarkably, the spouses are not buried next to each other. Amsterdam's Constantia Soreau was laid to rest in her hometown, but Cornelis is and remains a Vlielander through and through. On January 21, 1735, his body was sailed to Oost-Vlieland. The family again paid a fine of ten guilders for this (29).

Amsterdam City Archives, Fines on burials, archive number 343, inventory number 576

And on January 24 it is written in the books on Vlieland:

Received for the right of burial (a fine of) thirty guilders for the Corpse of Cornelis Vlaming brought from Amsterdam (Register of impost on marriages and burials Municipality of Vlieland, archive number 28, Collection DTBL - Tresoar, inventory number 0738, deed number 331. Found via Alle Friezen)

For that amount of money he may have been given a final resting place in the islander church? Or would he have been buried somewhere in the cemetery. Unfortunately it was no longer possible to find out. It is remarkable that all other bodies on the same page of the Vlielander burial book - eight in number - were buried pro bono. The only surviving son of Willem de Vlamingh had gone far. The joint heirs of Cornelis and Constantia had together about two and a half tons to divide.

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb