DEPARTURE

THE BEGINNING OF THE JOURNEY

Now the big journey can finally begin. We know quite well what the expedition members experienced from day to day on their voyage of discovery, because they - like all other skippers - kept a daily logbook. Arriving at the first refreshment point in the Cape, the three logbooks of the Geelvinck, the Nijptangh and 't Weseltje were transcribed by clerks and sent to Amsterdam (1). The same happened with the three logs about the continuation of the journey after arrival in Batavia. This is why the information about their trip to the Great Southland reached the VOC board in Amsterdam long before the expedition members themselves returned home to the fatherland (also because the skippers were immediately sent on another trip to carry cargo right after their adventurous journey).

Unfortunately, the original logs have not been preserved and the journals of the Nijptangh and 't Weseltje between the Cape and Batavia can no longer be found. To our great joy, however, the wonderful - and internationally acclaimed - National Archive in The Hague still has the copy, which was made in Batavia of Willem de Vlamingh's logbook and which he himself signed at the castle (2) .

So in summar: we have copies of the logbooks of all three ships between Texel and the Cape of Good Hope and only of the Geelvinck on the continuation of the journey between the Cape via the Southland to Batavia.

From these preserved copies we can conclude that the original diaries contained drawings made by Willem himself, because these were taken over by the copyist. For example, we find profile drawings of coasts in one logbook and the clerk of the other log has copied a cheerful ship with three masts. We assume Willem also had drawn a large ship with an anchor and a man on exactly the same spot in his original journal :-)

This drawing of a ship was on Friday, May 18, 1696, because that day they spotted a sail to the east of us around sunset.

We regularly see another symbol in the logbook: a thick cross, indicating someone has died that day. In total, on the three ships of this voyage of discovery - if we counted correctly - exactly thirty crew members died in just under a year (from departure from Texel on May 3, 1696 to arrival in Batavia on March 21, 1697). So a dangerous journey awaits the men!

THE NIJPTANGH IN TROUBLE

Just before departure, the Nijptangh already ran into problems. The ships were made at a shipyard in Amsterdam. In those days however there was still a shallow channel in the IJ between the capital and the sea: the widely infamous obstacle Pampus. Apparently the Nijptangh was overloaded, because on April 21, 1696 skipper Collaert already tried to sail the ship from the port of Amsterdam to the roadstead of Texel, but he got stuck on Pampus. He was probably in too much of a hurry to wait neatly for the so-called ship camels to carry his ship over the shallows. These were a kind of floating dry docks that were specially invented for Amsterdam in 1680 to safely bring ships in and out of the port. Usually people had to wait a few days for their help because of the crowds. It looked like Gerrit Collaert did not want to wait. He had tried it on his own and got stuck with the Nijptangh.

A so-called scheepskameel (literally translated: ship camel), a floting doc to lift ships a bit higher in the water so they could sail over Pampus, a notorious place to get stuck in front of the harbor of Amsterdam

First, the heavy goods on board the Nijptangh had to be transferred into a so-called lighter (a special ship intended for this purpose). There were twenty barges working as lighters in Amsterdam. One of them, as we saw, belonged to Willempie's father, who had his own ship as a lighterman. When their job was done, Marker fishermen came to pull the Nijptangh loose with their ships. In the end, the Nijptangh finally was able to continue its course towards the roadstead of Texel on April 25. There the hoeker joined the other two ships who were already waiting for departure. Because the wind had been in the wrong direction all this time, the whole venture was not delayed.

There on the roadstead of Texel the heavy items were brought back on board and the last goods, such as fresh drinking water, were also loaded. Even part of the crew was transferred in the last days before departure . They came with a couple of barges (called "kaag" in Dutch) from the Schreierstoren in Amsterdam to the waiting fleet at Oudeschild.

An example of a barge (called "kaag" in Dutch) the VOC used to transport their crew from Amsterdam to the ships in the roadstead of Texel. (Photo via Zuiderzeemuseum)

DEPARTURE

On May 3, 1696, the journey from the roadstead of Texel really begins. Remarkably enough, the logbook that Willem de Vlamingh kept tells us his wife Willempie and their children were still on board until the day of departure. That Thursday morning a barge came alongside with Commander Barent Vockes (the Flying Dutchman?) to wish the crew of the Geelvinck a safe journey. When the man leaves again, he also takes with him to the mainland my housewife and children whom were still on board with us.

So they all said their goodbye's not at home or ont the quai where Willem was boarding. We think it is a rather intimate idea to know the farewell took place on the deck of the ship Geelvinck. In addition to Willempie, at least the 25-year-old Evertje was present and probably the latecomer Aefje, who was only 8 years old at the time. Could these have been the only two children? Or were Trijntje, Hessel and Pietje still alive in that period? If so, they would have been 21, 20 and 16 years old respectively. All family members present also said goodbye to Cornelis, who stayed behind on board with his father on the Geelvinck as "third watch" (sort of third mate, after the rolls of skipper, chief mate and second mate) (3).

The departure of the ships did not go unnoticed. There is even one sentence about them in the newspaper called Oprechte Haerlemsche Courant of May 3, 1696, were it reads in Dutch: With the fleet to Greenland 3 Ships will sail to the Southland, one to Ceylon and some to Curassou.

Via

Together with a large fleet of other ships they sail out of the Marsdiep. This great event is described in detail in the logbook of one of the other skippers, Leendert van Deijl. On the first page of the log of his ship the Berkel, which has Ceylon as its destination, he writes they weigh anchor at five o'clock in the morning in the roadstead of Den Helder and leave with a southerly wind. The fleet consists of no less than 180 ships! Of these, 130 want to go to Greenland and 50 to London, New Castle and Hull. Of all those ships only some are mentioned by name, the expedition members to the Southland included. That is why we encounter the name of Willem de Vlamingh in this logbook.

National Archives in The Hague: 1.04.02, inventory number 5059, page 3

So nice to remember the 130 vessels heading for Greenland are former colleagues of Willem who will go on a whale hunt.

Among the large groups sailing to Greenland and England are three other ships that - just like our explorers - want to go south: the Berkel, the Winthont and the Maria. However, these six ships do not turn their prows to the south after departure from Texel. They set course to the north and sail along with the whalers. Because the Netherlands is at war with France at that time, they do not dare to risk the route through the canal and they opt again for the considerable detour around the north side of Scotland.

Whalers waiting for good wind at Texel (made by the great maritime artist ARNOLD DE LANGE)

On May 8, the Greenlandfahrers go their own way, even further north, leaving the three expedition ships, together with the Berkel, the Winthont and the Maria.

National Archives in The Hague: 1.04.02, inventory number 5059, page 15

On May 12, this small fleet of ships passes the Faroe Islands and the next day they reach the northernmost point of their journey. Finally they all can move south.

The three ships heading towards the Dutch East Indies remain close to the expedition members for a while. For example, the skipper of the Berkel reports on 17 May he sees the Geelvinck and sails towards her. On May 24, the skipper does not see any sign of the other ships, except of the Maria. On June 3, he notes in the margin of his log that they miss the Geelvinck, Nijptangh and the galliot again, which we still saw this afternoon. So they stayed fairly close together for about a month, but in the end the expedition members were on their one.

Court

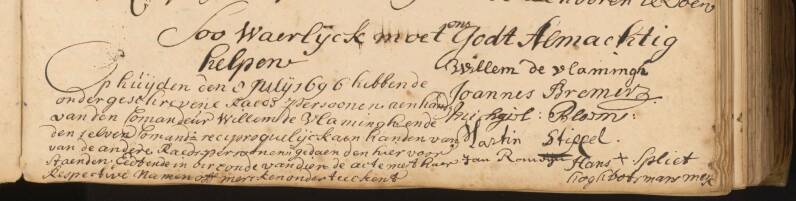

An incident took place on the Geelvinck on 9 July (4). A so-called midshipman (a young nobleman who is being trained as an officer) is told by the quartermaster he is not allowed to touch the pump. The boy probably wanted a drink, because quartermasters are in charge of food distribution on board.

The midshipman won't listen and an argument ends with the young man hitting the quartermaster in the face with his book - the Evangelium he was reading. Due to the blow with this bible, the quartermaster's face is injured and he complaints to the skipper.

In incidents like this, a ship's council was composed out of the six most important men on board, with Willem de Vlamingh as president. They formed a kind of court. Because the midshipman had never given any trouble before in the past, he received a merciful judgment: the boy had to stand in front of the mast and received 3 blows from all officers. Afterwards he even had to say thanks for this "merciful" punishment! The judges the judges hinted they were passing this verdict in order to keep the peace on board. Willem was one of the men who signed the statement. Looking at his unsteady signature we can deduce he preferred to hold a tiller rather than a pen!

See Grootboek en Journaal van de Geelvinck (National Archives in The Hague, 1.04.02 - 5435, page 366)

A ship's council had also been held three weeks earlier. The cook's mate, one man named Jan Andrez van Amsterdam, did not do his job properly and was demoted to soldier. On that particular day, June 17, they had already been sailing for more than six weeks and apparently there were complaints about his functioning. One of the soldiers was then appointed as a new cook's mate and his salary immediately went up considerably (from 9 to 14 guilders a month) (5).

Tristan da Cunha

On its way south on the 9th of July 1696, the Nijptangh lost contact with the two other boats of the expedition. In the letters later sent from the Cape to the VOC in Amsterdam, we can read what happened to the various ships.

The registers of the VOC state the Nijptangh became separated from his friends, but skipper Gerrit Collaert still wanted to visit the island of Tristan d'acunha because he had received this instruction in the Netherlands. The Nijptangh already reached the archipelago on August 12. Although they could approach the isles very closely - according to the daily records kept at the large VOC castle in the Cape of Good Hope - they did not manage to set foot on land, because they were not able to find any anchorage. Due to the heavy winds, the rain and foggy weather, they had to leave the place empty handed on August 16 (6).

Just one day later the Geelvinck and 't Weseltje arrived at the archipelago. Like the crew of the Nijptangh, they also initially failed to find a good anchorage. The next day, however, Willem de Vlamingh himself went along in the sloops and he succeeded!

Part of the Tristan da Cunha Islands as drawn in the logbook of Willem de Vlamingh

(National Archives in The Hague, 1.04.02, inventory number 5060, scan no. 12)

This venture was undertaken by Willem personally on August 19, and rowing along the rampart they found a hole in the mountains, having the figure of a ruined city gate. There they moored the sloop and so the men could climb ashore.

The group of researchers found a totally barren island with only some marram or long grass and in between an unknown herb. The island had steep cliffs, which were overgrown with tall trees. These cliffs seemed inaccessible and therefore it was not possible for them to pick up some firewood.

They did find fresh water and a very large crowd of penguins. These animals were so tame, they let themselves be caught by hand. The sea around the Tristan da Cunha-islands was also very rich in fish and, in their opinion, it was safe to sail around it, because they did not see any clippings, reefs or droughts. On the contrary, the water seemed spacious and clean.

Willem proposed the VOC should have another ship come back in the summer time for further discovery. Now the expedition members had to much heavy wind, rain and fog. Moreover, he could not stay longer, for his appointed time of arrival was already overdue. They hurry to the refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope. Not a day too soon! Because due to the bad weather conditions and the lack of fresh food, manyof the people on board had gotten sick already.

The ill

From the trip between Texel and the Cape we have no fewer than two notebooks with information on all the sick, kept by the doctors on board (7).

From these documents we can learn the crew members suffered from all kinds of different illnesses and what medicine were prescribed back then. For example, the watermaker had been complaining about dysentery for eleven months and the carpenter suddenly got a heart attack. All of a sudden he fell backwards, quick salt did not help anymore and the poor man was gone.

After a while at sea, they all contracted scurvy. One comes with a smelly mouth and black rotten gums, so he is allowed to rinse with brandy. Especially the men who had not received warm clothes from the so-called soul sellers (see the chapter Before the trip) all caught a cold from the wet cold weather.

For colic, the doctors used elixirs, and the cobbler drained six ounces of blood. Most patients are given a soft-boiled egg and a glass of seck as medicine.

Zie Nationaal Archief 1.04.02 inventarisnummer 5060, pag. 26: The translated text reads: Journal of the sick and patients who arrived on the Journey from Texel to the Cape of Good Hope in the hands of Me Gerrardt Hardenbergh chief master on the ship the Geelvinck, commanded by Willem de Vlamingh (1696)

Zie Nationaal Archief 1.04.02 inventarisnummer 5062, pag.37: in translation: Copy of the register by the chief surgeon of the Hoecker, the schip the Nijptangh

Another example of a typical case on board:

The surgeon is called to a sailor from Lübeck, who complains of pain in the head, arms and legs. To fix this, the doctor first makes him sweat by administering a certain drug to the boy. The next morning the sailor feels a lot better, but towards the night the pain returned. The doctor then asks him if he had been with “unclean women”, what the boy did not want to admit to, according to the physician. In the end, the sick sailor remains in his bunk without speaking until he dies. When the doctor undressed him afterwards, he found on his preputium (the posh word for foreskin) a slightly yellow and greenish substance. The surgeon concluded that the cause of death was indeed a venereal disease, something the sailor had never wanted to admit.

Both skipper Willem and his son Cornelis seem not to have been treated by the surgeons during the first part of the journey between Texel and the Cape. They also do not appear in the list of crew members who suffered from scurvy. Perhaps the food in the cabin was slightly better than the food for the rest of the crew.

The name of Cornelis de Vlamingh does appear in the list of men who received a bonus. He saw the Cape of Good Hope first and received 6 Spanish reales (8). Captains offered these rewards so everyone on board was on the watch and they didn't just sail past lands and shores.

See the National Archives in The Hague. VOC: 1.04.02, inventory number: 1587, page 518, (= scan 530).

On this page of the VOC it is stated 6 Spanish reales have been paid out to the "third watch" (fouth mate) Cornelis De Vlaming because he pointed at the Cape first. Funnily enough, in the Ship's Salary Books of the same VOC it says: on September 5 third watch Cornelis de Vlamingh from Vlieland only earned 5 reales as a Primo for seeing the Land of the Cape of Good Hope.

How much would it have realy been? According to this last text, it was in any case worth 50 stuijvers (ie 2.50 guilders).

Nationaal Archief in Den Haag, 1.04.02, inventarisnummer 5435, scan 401

Maak jouw eigen website met JouwWeb